I’ve been out of the underwater photography game for a decade now, so it doesn’t happen very often anymore. But people who knew about my hobby used to come up to me at parties or corner me at some tropical resort and ask the question. Or sometimes people on dive boats, inexplicably undeterred by watching my toting, fixing, and cleaning of heavy, expensive, delicate, and fickle equipment, would ask it:

“How do you get started in underwater photography.”

I had a stock answer. Nobody ever liked it.

“First, get a hundred dives in your logbook.”

Sometimes, they stuck around to hear my reasons.

First, there are the dangers to yourself and your buddy.

Perhaps the biggest dangers are to your buddy. Photographers as a group make terrible buddies. Being a good buddy means having good situational awareness; knowing where your buddy is and if she needs anything at all times. That’s hard enough if you aren’t too experienced and have no camera in your hand. It becomes nearly impossible if you’re trying to make pictures with little experience. In fact, photography demands so much attention that I don’t think you should be taking pictures underwater unless your buddy has 100 dives, too.

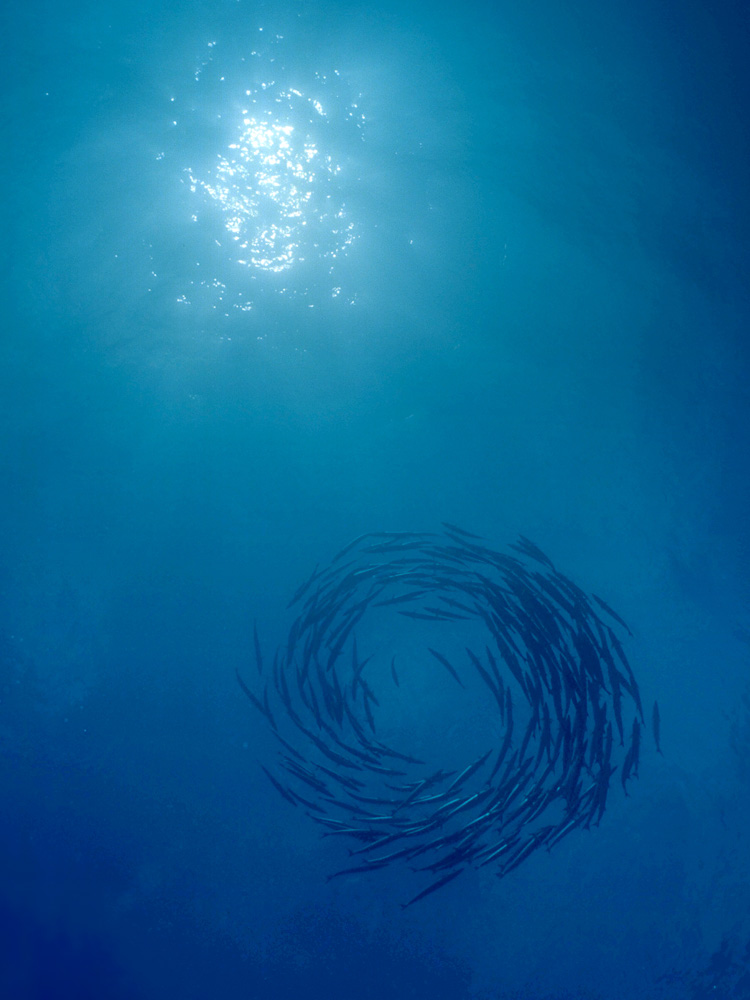

Even setting your buddy’s well-being aside, there’s keeping yourself out of trouble. Keeping track of where you are and how to get back to the boat is sometimes tricky if you’re paying full attention. People who aren’t distracted by a performing moray have been known to lose track of their nitrogen loading, their air supply, the changes of tidal current, and all manner of details that are important to survival and not ticking off everyone on the boat with a trip to the chamber or a search for your sausage.

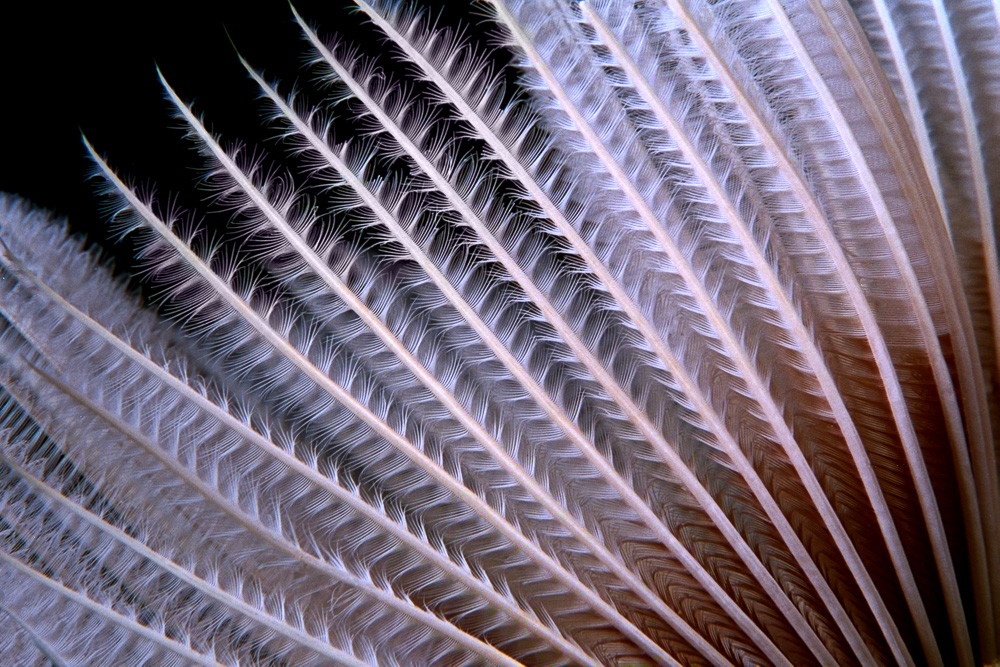

Then there are the dangers to the beautiful places where you dive. Inexperienced divers lose track of their buoyancy and crash into things even without a camera. Buoyancy control has to be second nature before you encumber both your mind and your hands with photographic equipment. If you are trying to set up for a shot, you are much more likely to flounder around and stir up the bottom than someone who’s just sightseeing. When that whale shark shows up and you’re trying to get the camera set properly, unless you know what you’re doing the current is likely to slam you into the reef.

Divers, you probably get the idea. But what if you’re a snorkeler?

Same thing, only maybe more so, since snorkelers – not the ones who free-dive to 60 feet, and spend 2 minutes down there, but the mere mortals – often find themselves in conditions where there’s a lot of surge. If you’ve get a reg in your mouth, you can go down and get away from it. If you’re a snorkeler, you’re stuck with it. That means there’s even more of a chance that you’re going to get tossed about by the ocean, and, if you have a camera in your hand, even more of a chance that you’re going to tear up the reef.

Leave a Reply