[Added 7/3/17: In this post, I am using the word criticism to mean the art or practice of judging and commenting on the qualities and character of photographic works. I don’t mean the word to imply that the comments are negative, although I clearly want to include that usage. In a comment below, Mike Nelsen Peddie suggests that a distinction be made between criticism and a critique, which I will define to be a detailed analysis and assessment of a photographs or body of work.]

I recently had an acrimonious encounter with a fellow photographer on DPR. He said that he wouldn’t use cameras with pixel counts of less than 50 MP, and I said:

Placing arbitrary limits on your equipment is potentially injurious to your photography. Pick what you want to do, then use the tools that are available. For many things, 50 MP is completely unnecessary: small and medium-sized prints, web use, newspapers and most magazines. It won’t always be thus, but placing a 50 MP lower limit on your camera means that you can’t use the a9, D5, a7RII, or a host of other cameras that have use envelopes that go places where >=50MP cameras can’t. Maybe you don’t want to go there, but limiting your options by camera specs is putting the cart before the horse.

The reaction was intense. The photographer took the position that he, and he alone, was the judge of what was right for his photography, and that my statement was offensive, condescending, and inappropriate.

As is usual with Internet interactions, the exchange made me reflect on a few things. One of them was the place for criticism in the development of one’s photography. I’m not talking about arguments about whether something stated as a fact is true or not, but about more general comments about how to become a better photographer. (Another issue arising from this, oh, let’s be generous and call it a conversation, was something I’ve written about here several times before, the place of limitations in photography. I’ll be posting something on that in the future.)

I’ve been at this game for a long time, and I’ve gotten suggestions, comments, questions, and both pointed and supportive criticism of my photography from many people whose names you’ll recognize: Ansel Adams, John Sexton, Huntington Witherill, Morley Baer, Ruth Bernhard, Charles Cramer, Ted Orland, David Bayles, Pirkle Jones, Chris Newbert, Brooks Jensen, George Tice, and Chris Ranier. Most of that was solicited. I’ve also had my work critiqued by hundreds of other people: the participants in every workshop I’ve ever attended. I guess I requested that just by showing up. I’ve also received unsolicited advice on what I ought to do from many folks who I encountered in my photographic travels. I’ve attended PhotoLucida twice, and that’s a veritable orgy of criticism, both from the paid famous names and all the other participants. I am a member of a photographic society, ImageMakers, and we subject ourselves to monthly face-to-face mutual critiques. I’ve gone to many of those.

And then there’s the Internet. I’ve got a web site with photo galleries, and people often send me messages telling me what they think. No one seems to hold back in discussions on various boards, either.

So I’ve been criticized a lot, both when I’ve asked for it and when I haven’t. It’s not always pleasant, but what I’ve found is, if you look at it the right way, that it is nearly always useful.

Let me give you an example. I interviewed Linda Connor for the CPA newsletter, Focus, in 2004. She had done a portfolio review for me at a Friends of Photography event in the 1980s, and, although I wasn’t in synch with her kind of photography, she gave me feedback that was immensely insightful and changed the way I looked at some things. So when I went to Mill Valley for the interview I brought along a box of prints from the project that I was working on at the time, which turned out to be This Green Growing Land.

Linda didn’t like the work at all. The way she looked at it, the problem wasn’t in the execution of the series. It was worse than that. The project was flawed in its conception. She told me that I was doing a disservice to the farmworkers by making their gritty, backbreaking labor look beautiful.

She didn’t buy my concept for the series, which was a stripping bare of specifics to make the workers archetypal and their work majestic, in the style of Diego Rivera in his American Depression-era murals. She gave me a book called, With These Hands, with photographs by Ken Light and an introduction by Cesar Chavez, that portrayed farm workers in the same location in a photojournalistic style as an example of what I ought to be striving for. The photography couldn’t have been more different from mine. Low-contrast, seemingly unmanipulated, black and white documentary images. No beauty here; these pictures were ugly by design. I’m not taking anything away from Light; I’m sure they were just what he had in mind for that project.

I didn’t want to hear what Linda had to say. I didn’t argue with her. What was there to say? She had her opinion, and I could see its validity, and we’d just had a small argument over my opinion that Bob Dylan’s lyrics were vague, and she’d been unimpressed when I quoted Joan Baez as someone who ought to know who shared that view.

I thought about what she said for a few months. In the end, I was comfortable with what I was doing with the series. Part of the reason was the reaction of many of the students at Hartnell College, where I’d had an exhibition the previous year of the beginning of the series. Many of them were sons and daughters of the field workers, and quite a few brought their parents into school so that they could see what their work looked like through my eyes. That seemed nice at the time, but it assumed new importance in light of what Linda had said. I didn’t change my photography based on Linda’s comments, but they provided me with a context and an alternate perspective that enriched the work for me.

There’s a lesson here. You don’t have to accept criticism for it to be useful. You don’t even have to pick through it looking for things with which you agree. Here’s a case where I ended up not changing the direction of the work at all, but Linda’s point of view still brought depth and nuance to the way I thought about the project.

Sometimes criticism can be embarrassing. In the 1980s remember showing some silver prints of a then-new series in the Stanford Hills to Ruth Bernhard and John Sexton. John said, “You just used Potassium Ferricyanide, not Farmer’s Reducer, right?” I asked John how he knew. He pointed out a faint yellow stain. I hadn’t seen that, but it suddenly was obvious. I could see it in every print that I’d bleached. I was mortified. I went home and reprinted all the afflicted work, thankful that I had not sold any prints or exhibited any of the images. I owe John an immense debt for saving me from sending crucially flawed images out into the world.

Sometimes, criticism comes in the form of questions. Over the years, I’ve gotten used to these, and I think that applying a form of the Socratic Method to critiques is an excellent way for teachers to teach and for students to learn. Some of the questions are general and more-or-less standard, for example,

- Why did you pick this subject?

- How did you get to this treatment?

- How does what you’re doing relate to what you’ve done in the past?

- Did you get ideas for this from other photographers? Which ones?

- How do these images make you feel?

- How do you want your viewers to feel when they look at them?

- What are you trying to say?

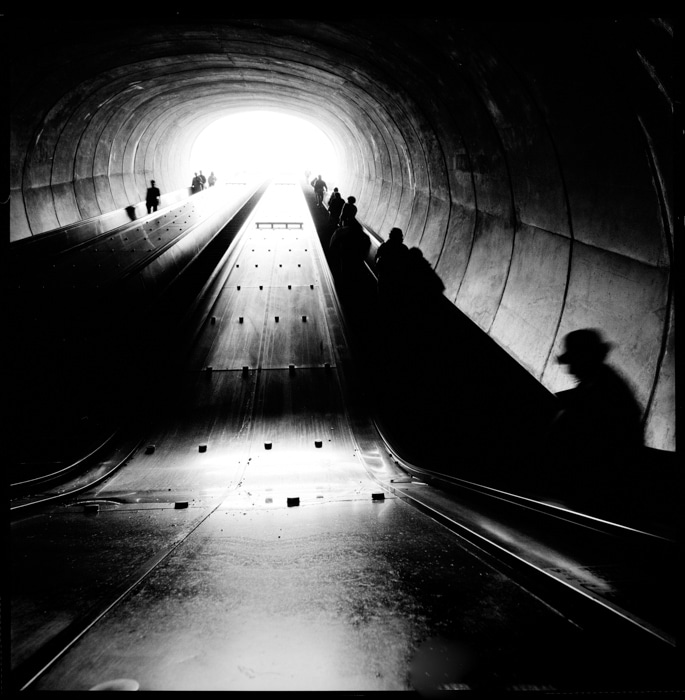

Sometimes criticism is specific to the work you’re showing. I once showed some of the work that became Alone in a Crowd to a teacher (whose name I’ve forgotten, sorry) at the San Francisco Art Institute.

He asked me an interesting question, “Who gave you permission to use motion blur that way?” That made me think. The motion blur was a defining part of my concept of the series, but I’d never considered where I’d gotten the notion that that was a good thing to do. I’d fallen into it from being in situations where there wasn’t enough Iight to stop the motion, deciding that it could be satisfying if there were just the right amount, and running with that. I went home and spent some time looking at books of photographs to see where I’d inadvertently gotten the background for the style that I used in that series. It was instructive.

Photographers can do things over and over to the point where they anesthetize themselves to what they’re doing. For the most part, this results in problems caused by overdoing things; rarely is the issue that the images are undercooked. Often a third party can point out things to which you’ve become desensitized, so that you can make corrections – if you don’t know you’re doing something, you can’t stop doing it. One of the greatest examples of understatement in landscapes are the photographs of Stephen Johnson. I’ve done a couple of workshops with Stephen, and it’s like a trip to the fat farm. Afterward, I’m much more conscious of respecting the base image, although I never go completely to the subtlety of the way that Stephen does it.

So far, I’ve talked mostly about criticism solicited from an authority figure. Often, I get criticism that I didn’t specifically ask for. People send me emails about what I post on this blog and in my galleries. Most of those e-missives are supportive, some of them are not, and a few of them are hostile. Facebook is an environment where I get no antagonistic reactions, but plenty of suggestions and comments. When I post images on DPR or LuLa, I get many responses. I think that, by the very act of posting pictures on the Internet, I am saying that it’s fine to critique them. I suppose I could ask that people hold their comments, but I’ve never considered it; it seems like two-way discourse is part of the totality of the web.

One of the results of all of the above is that, in many ways and in many settings, people have told me what they don’t like about my work. Sure, I get lots of strokes, too, but the negative responses are for me the opportunities for growth. They show me where I haven’t communicated what I’m trying to communicate, where the aesthetics that I’ve chosen don’t appear as compelling to others as they do to me, and where I’ve fallen into the trap of the commonplace image.

In a technical discussion, when someone disagrees with me, I am not threatened. I see it as an opportunity to learn or to teach, and I have to figure out which it is – often it is both. I think I have that attitude from so many years as an engineer. I learned early on that if you weren’t going to learn from disagreement, then you weren’t going to learn all that much, and that’s a good way to become a mediocre EE. Now that I’m retired, I have learned a great deal about photographic technology from DPR and LuLa participants and others, a few of whom I’ll publically thank here: Eric Foss, Eric Chan, Jack Hogan, Bill Claff, Marianne Oelund, Frans van den Bergh, Nicolas Robidoux, Bart van der Wolf, Joe Holmes, Mike Collette, Nick Wheeler, Brandon Dube, and Alan Gibson. There are others I know only by their user names, like DSPOgrapher and Horshack on DPR.

But I have a harder time dealing with negative criticism about my photographs.

Here’s an example:

this week’s scans are about the ugliest, gloomiest, dark, and uninteresting photos that I have ever seen posted here on this forum. You like playing around with that stuff that’s fine. I think you should limit posting pictures and give advice about technical things.

My first reaction is often that the critic doesn’t understand, is confused, or is just plain wrong. That’s not a useful perspective. What I’ve learned to do is:

- First, wait. Don’t come right back with an explanation or self-justification. Let it soak in.

- Then look at the emotions that you have. Don’t try to feel differently, but ask yourself why you feel that way. You will probably learn something from the answer.

- Then talk to the critic – if that’s possible – and make sure you understand where they are coming from. You don’t want to learn from a mistaken appreciation of what the issue is.

- Don’t get too hung up on whether the criticism is right or not. Ask yourself what you would do if it were right. The idea is to se what you can get out of the criticism; don’t treat it like a you’re right/I’m wrong thing.

- After you get your head around the criticism, live with it for a while. Let your right brain process it. Do some research if you think that’s useful. Then let it sit some more.

Then do what feels right. You may find that your work changes in subtle ways with no conscious decision on your part, just because you now look at things differently. You may find that nothing changes, but at least you gave it a chance. It’s even OK to conclude that the criticism was unwarrented and the critic was a jerk, as long as you get what you can out of what she said.

You can’t go through the whole rigmarole for every little negative zinger, but with practice, you’ll be able to decide which comments are worth the effort and which are not.

There’s another kind of criticism. It’s not negative; in fact, it’s usually positive. It happens when someone comes up to you at an opening or speaks out in a group review with something like: “I really like the way you…” and comes up with something you never even thought of. It’s kind of weird being congratulated for doing something you had no intention of doing, but it’s not that unusual, at least for me.

Get used to it: photographs, like all art, are a kind of Rohrshach test, and what people get out of them depends in large part on what they bring to the experience, not what you put in the picture, and especially not what you thought you put into the picture. But you can learn things about your work from what other people see in it, and you shouldn’t just brush off those kinds of comments.

Herb Cunningham says

I think Guy Tal hit it on the head when he said that the work is an expression of the artist. It says what the artist felt was needed to be said.

Any other opinions are just that, opinions,.

Most of us who do not need to make a living from our work do not need approval from all corners, indeed, that would be a danger sign, IMHO.

JimK says

Herb, I agree that we need to be true to ourselves. From Art and Fear:

“Art is often made in abandonment, emerging unbidden in moments of selfless rapport with the materials and ideas we care about. In such moments we leave no space for others. That’s probably as it should be. Art, after all, rarely emerges from committees.”

However, there is a rich tradition of photographers learning from other photographers, and I think that’s a good thing for the teachers and the students, and for photography in general. I don’t think John Sexton, Don Worth, Ted Orland, Alan Ross, Chris Rainer, and many others would have been the photographers they turned out to be if Ansel hadn’t taken them under his wing. In looking at the history of Group f.64, it appears that most all of those people learned from each other — with the possible exception of Edward Weston and learning. That mutual education continues in person in the Monterey Bay area to this day, and I think it’s valuable for all concerned.

Remember the Cremona analogy in Art and Fear? Ted Orland, David Bayles, Brian Taylor, Saelon Renkes, and some others have for decades been part of a group that meets every couple of months to show each other work, to talk about their work, and to hear what the others have to say about thier work. Everyone in this group to whom I’ve talked say that it has been invaluable in their development as artists.

Christer Almqvist says

I’ll have to come back and re-read it in a week’s time. Will be worth it.

Herb cunningham says

Jim, agree we need others to grow- been of follower of Ansel Adams since the 60’s and have way too many photographic books. I think my reaction to Guy is more along the lines of liking a picture I made even though others don’t like it.

I imagine we all have those around, I have at least two; I love em, nobody else does.

Mike Nelson Pedde says

A thoughtful and well-considered discussion. I would only add that (to me at least), there’s a difference between a criticism and a critique. Everyone gets to have an opinion, and everyone is entitled to his or hers. There seem to be those who feel that everyone else is also entitles to theirs; for my part I tend to avoid/ignore such people. If you say, “This work is crap!” that your opinion and you’re welcome to it. If it’s my work you’re looking at, odds are I disagree with you.

In my experience people looking at art usually have a visceral reaction first – they like it or they don’t. I encourage new photographers to go beyond that, to question everything they like or don’t like, to find out why, and to ask how they would have done it differently. That to me is the basis of critique. Do it with others’ work, but be even more critical of your own… that’s the path to improvement. In my opinion, of course!

JimK says

I was using the word criticism in the sense that an English major might when she says “literary criticism”. But my main point was that it doesn’t matter if the critique or the criticism is well considered or not. It’s not important if there is any merit to it or not if you can use it to move forward. And yes, after you’ve given it some thought, it’s perfectly OK to decide that the critique was BS.

Jeff Wayt says

Chris Ranier and I graduated from the High School For Performing Arts, class of 1976. I haven’t seen him since then, but we are all very proud of him and all our alumni, including Mark Seliger (c/o 1977). Small world.