This is a continuation of a report on new ways to look at depth of field. The series starts here:

If you’re coming late to this party, here’s some background on object field methods.

It is a tenet of the object-field (OF) approach to depth of field (DOF) management that resolution is constant in the object field when the lens is focused at infinity. Proponents of OF methods recognize that diffraction will keep this relationship for holding at great distances, but offer little quantitative guidance as to how to deal with it as it breaks down.

In the past, I posted an examination of the object field behavior of an infinity-focused lens, but my lens model was not very accurate wider than f/8. Now I have a new, more accurate way of simulating the combination of diffraction and defocusing (thanks, Alan) and two new lens models, one for the Zeiss Otus 85/1.4, and one for the Nikon 85/1.4 G.

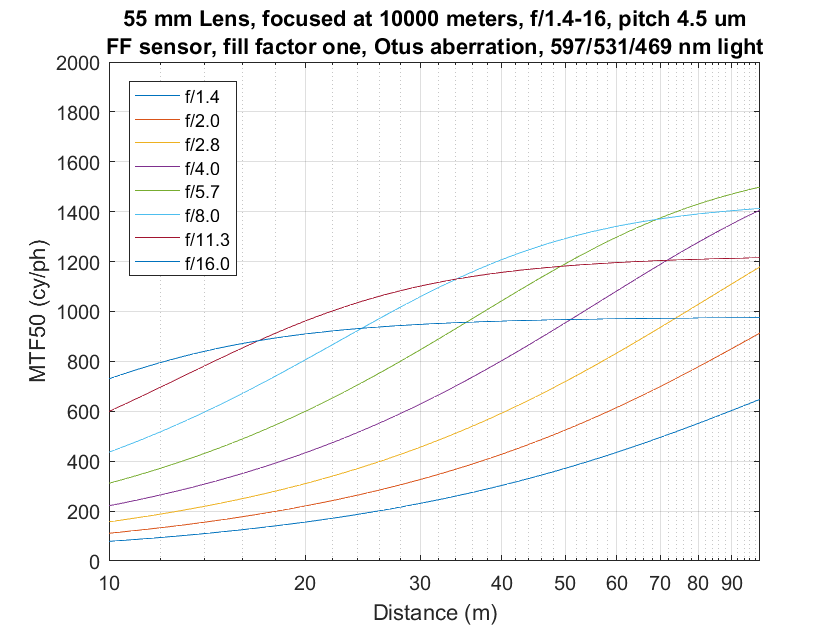

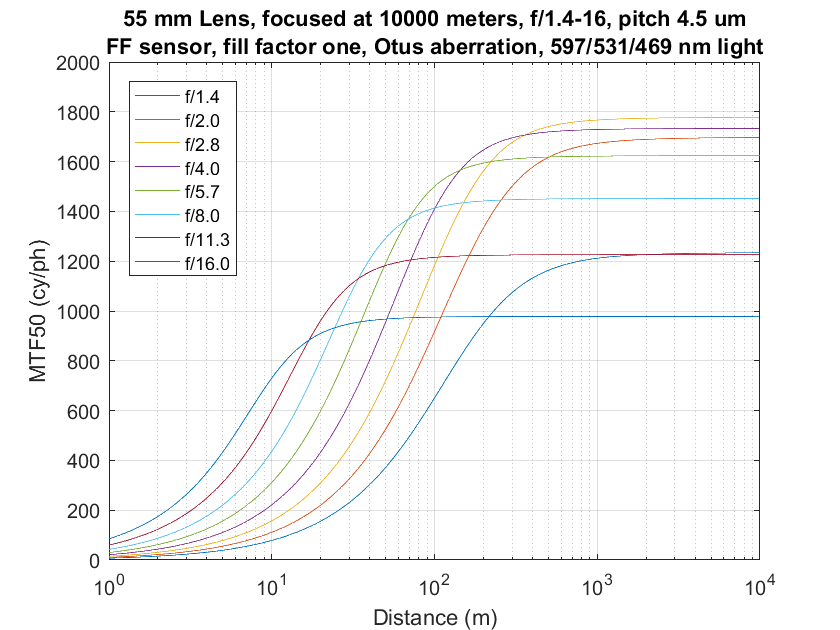

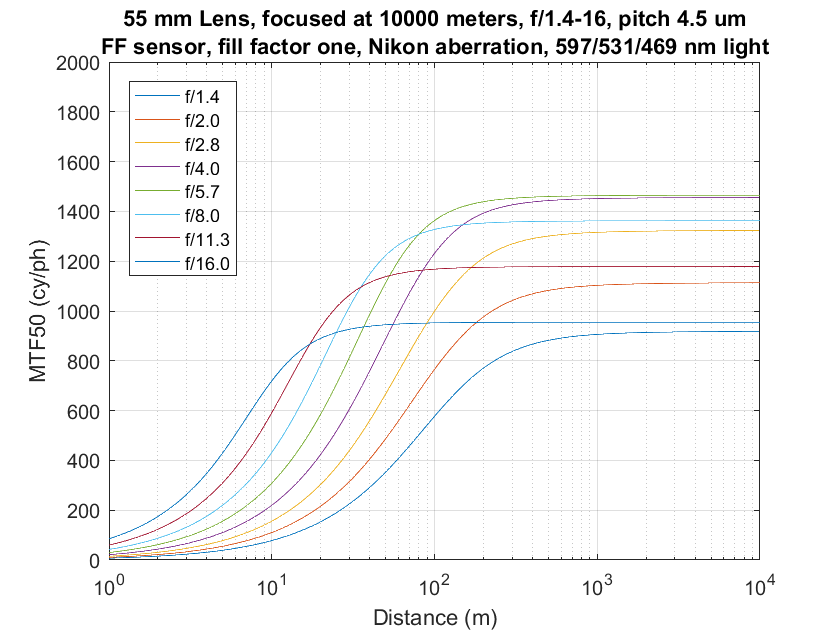

First, let’s repeat a couple of image-plane images from yesterday’s post, but with legends that make it easier to tell which curve is which. I’ve scaled the focal lengths of both lenses to 55mm.

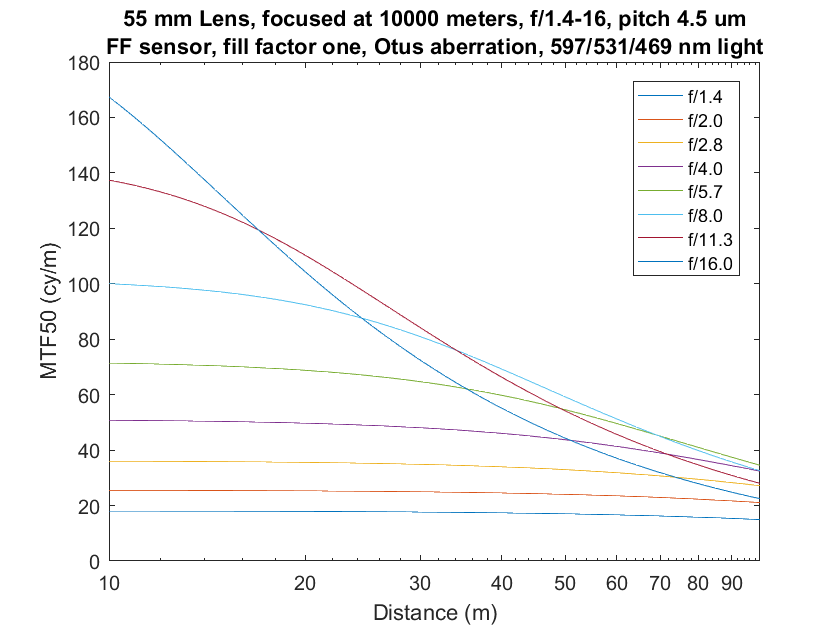

In the object field:

You can see that the predicted object field behavior occurs, but only at short distances.

If we call 800 or 1000 cycles per picture height the edge of photographic sharpness, then the transition region from blurred to sharp takes place with the subject between 10 to 100 meters. So let’s take a closer look at just that region.

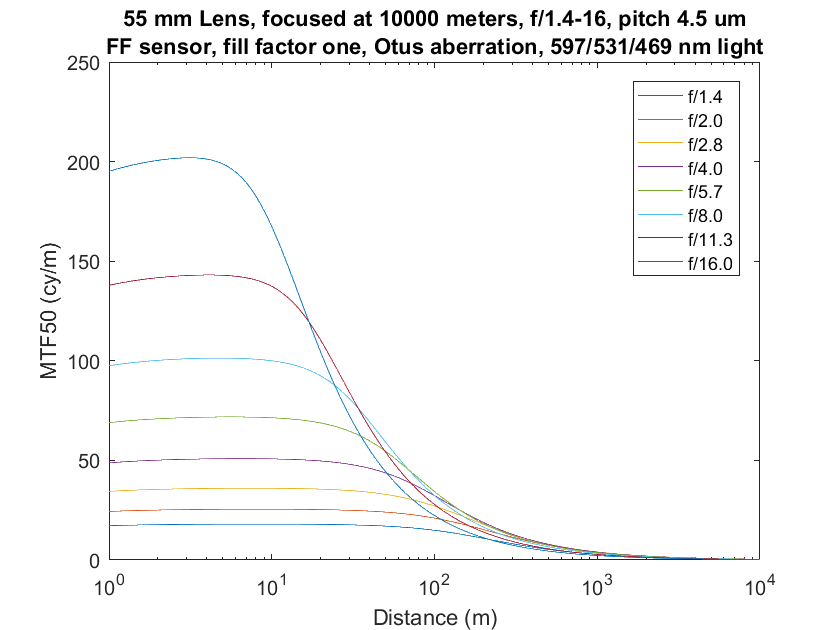

First, both fields for the Otus.

The object-field lines are pretty flat for (going from bottom to top of the object field graph) f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, and f/4. But if we look at the image-plane plot, we can see that, at those f-stops, we have sharpness that is pretty soft up to 50 or 60 meters. The f/11 and f/16 object-field lines are never flat, and the f/5.6 and f/8 lines start falling when the sharpness gets to the photographic region.

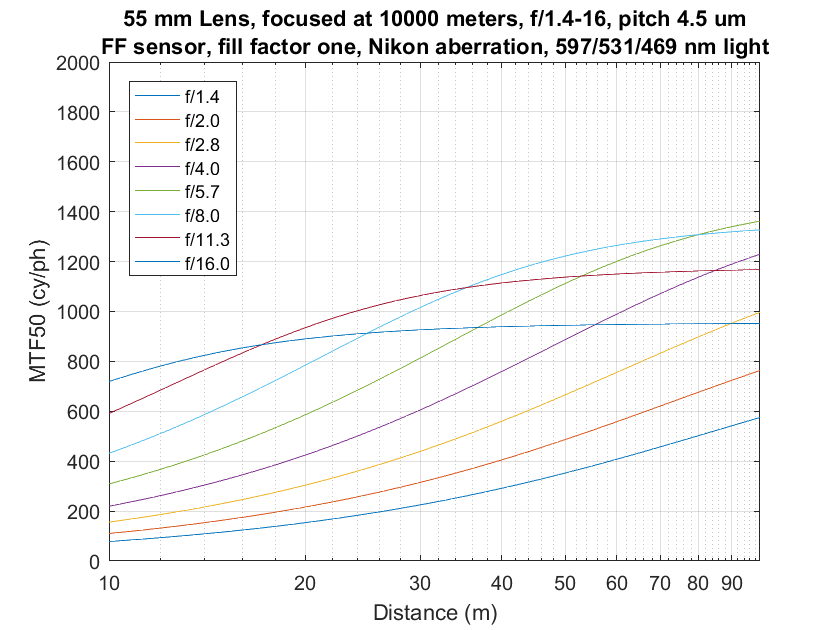

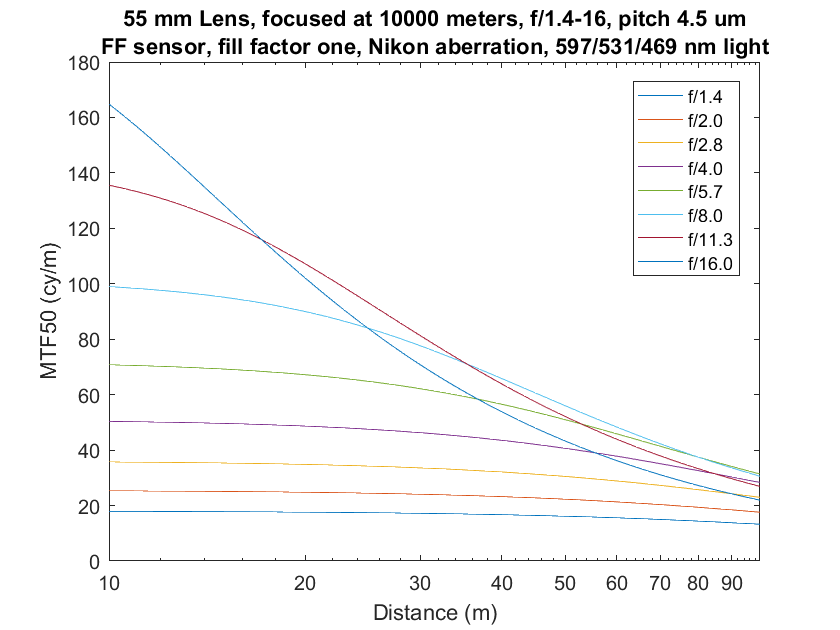

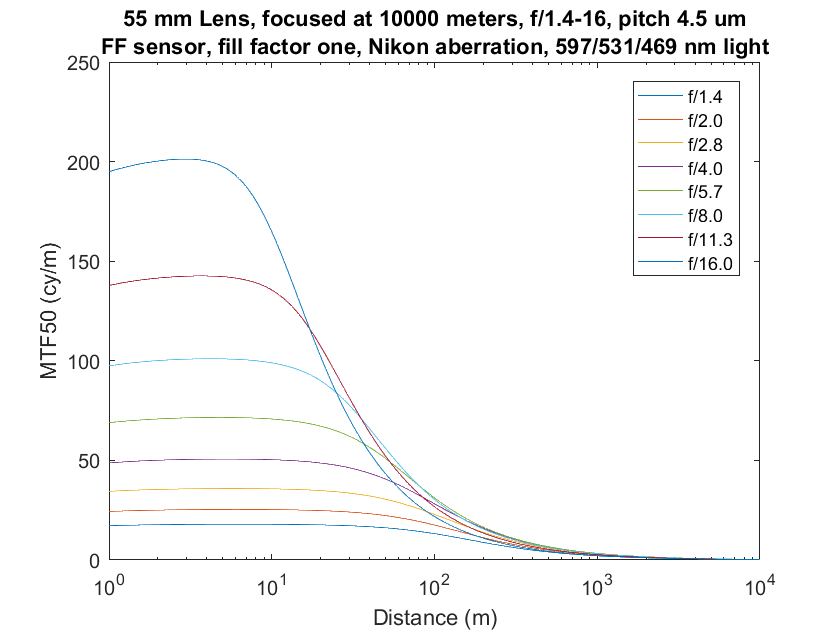

With the Nikon lens:

The same kind of situation obtains, but the conformity to the OF dictum is even worse if you care about photographic sharpness.

It looks to me that the object field rule of constant resolution is only adhered to in regions of noticeable softness. That doesn’t mean that the rule is not useful, just that it should be applied to managing degrees of critically-visible blur.

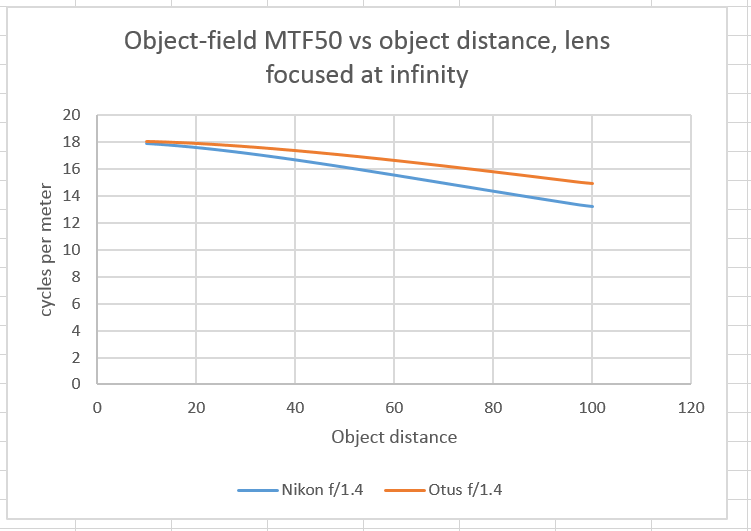

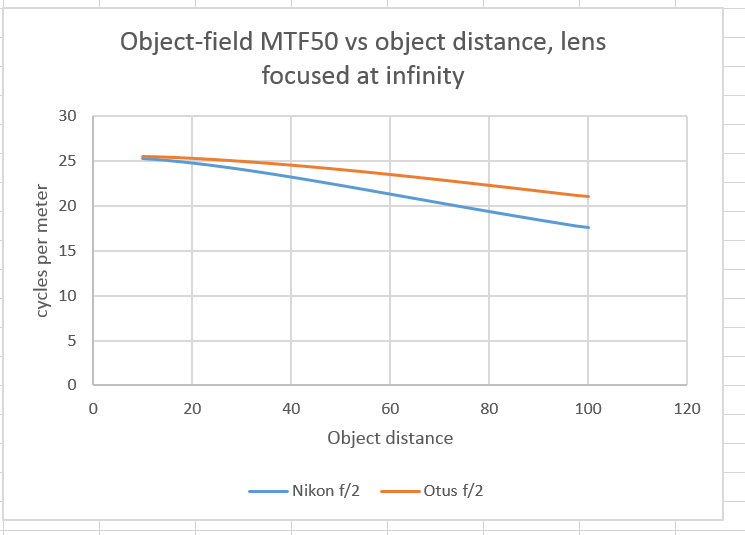

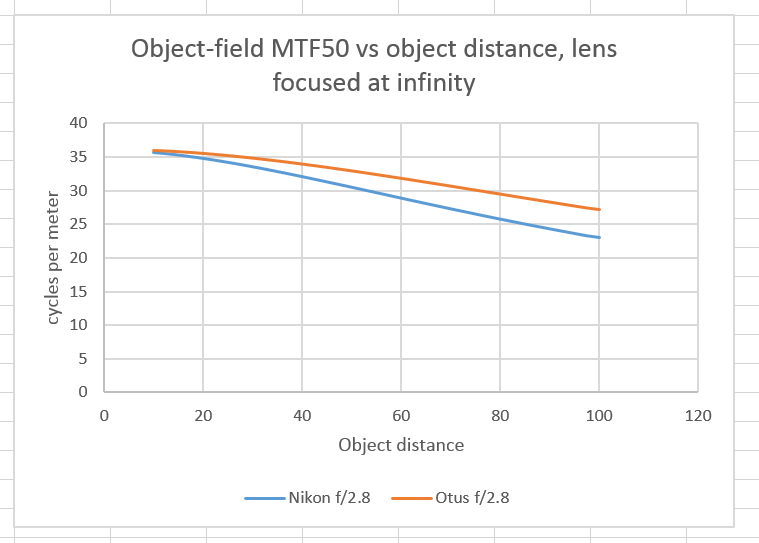

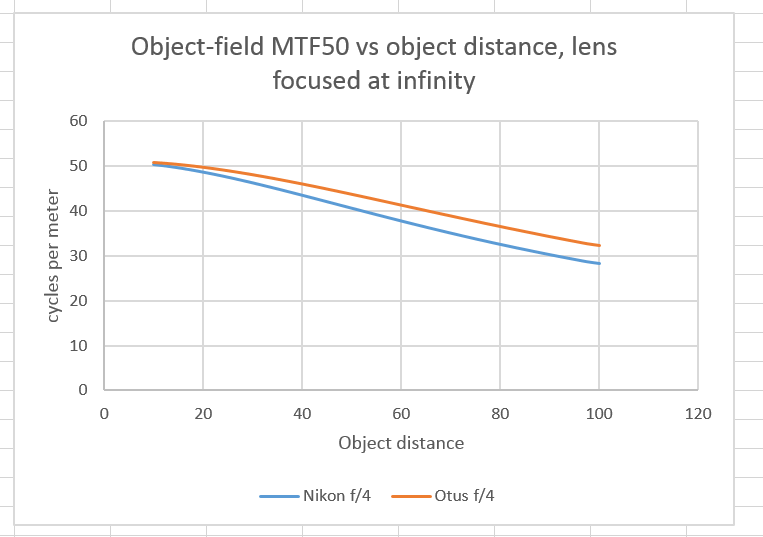

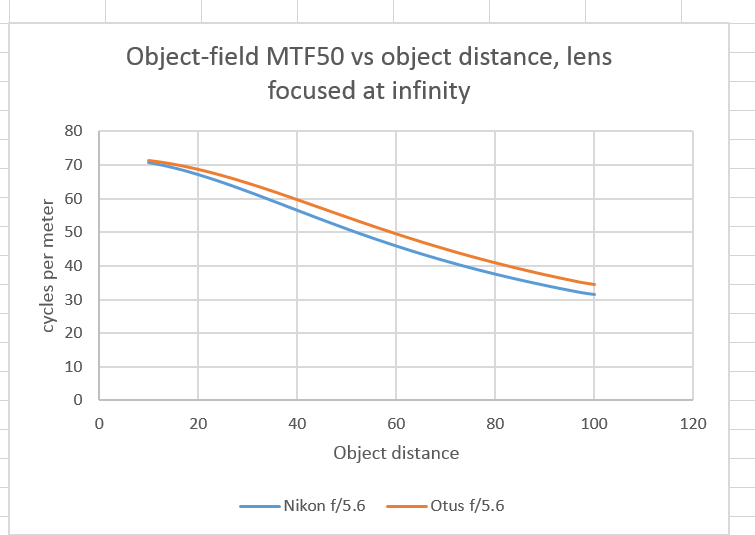

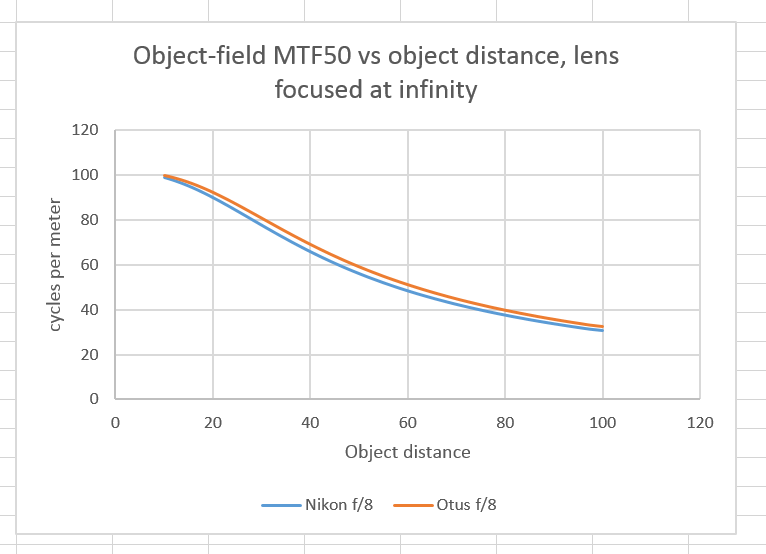

You can get another cut at what’s going on by looking at the two lenses’ results on the same chart one f-stop at a time.

At near distances, the sharpness is identical, because it is dominated by focus. At further distances, there is more falloff in sharpness with the Nikon.

Same thing, only more so at f/2; that is close to the Otus’s best performance.

Same.

Now diffraction is becoming more important, and it affects both lenses equally, so the difference is diminishing.

Diffraction is more important.

At f/8 and narrower apertures, it’s all about diffraction.

Leave a Reply