In the last three posts I’ve dealt with photographic subjects that have some degree of specularity. It occurs to me that some readers may not understand the concept well, and if they do understand it, they may not be able to relate the concept to their photography.

Hence this post.

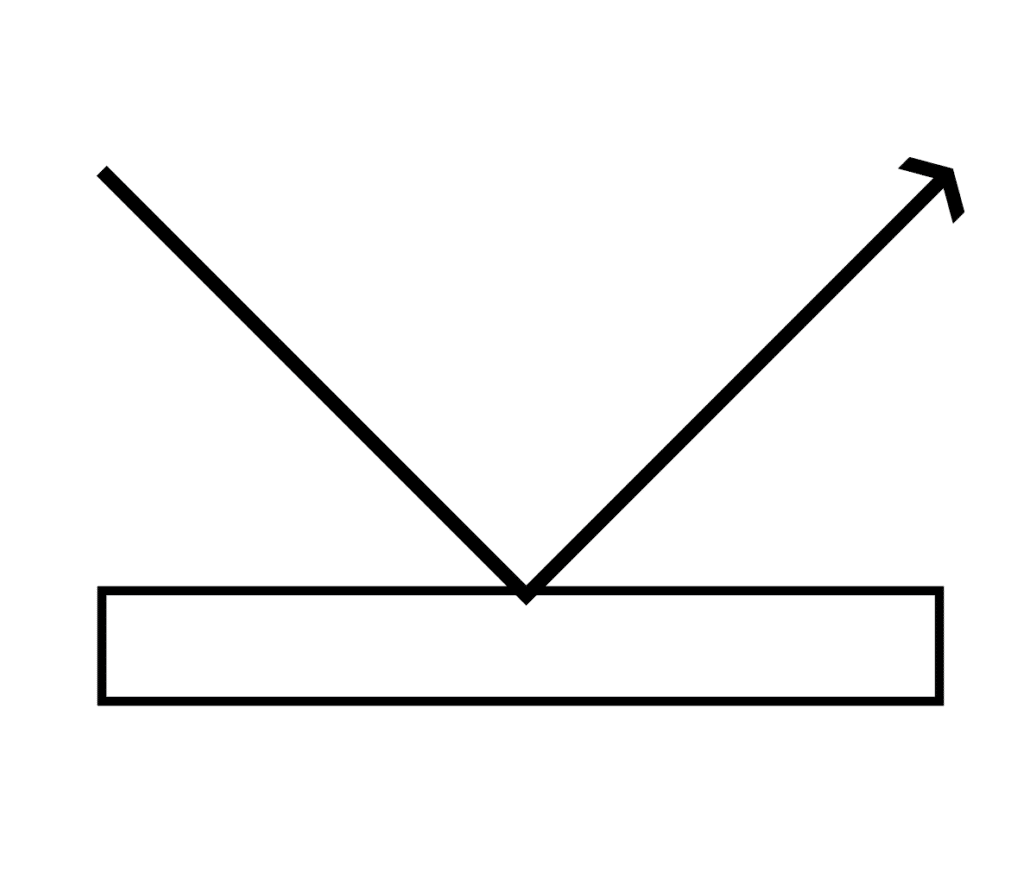

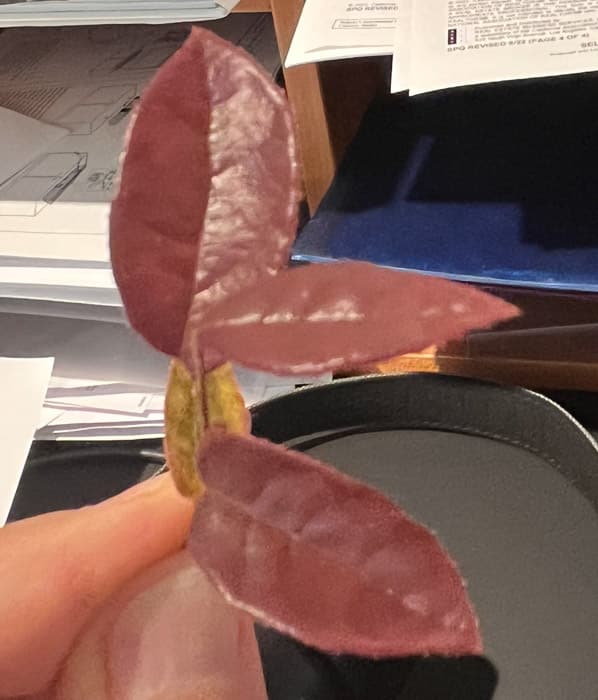

In general English, specularity is defined as “the state of resembling a mirror”. In photography, a surface is called specular if it’s shiny, and if light hits it at the right angle, you can see any reflection of the light source — called a specular reflection. The opposite of a specular reflection is a diffuse reflection, or, if you want to get technical Lambertian diffuse reflection. A Lambertian surface reflects light so that the apparent brightness of a Lambertian surface to an observer is the same regardless of the observer’s angle of view. A perfectly specular surface reflects light so that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection.

In normal photography, as opposed to the lab, reflections are rarely purely specular or purely reflective, but somewhere in between.

Let’s look at some examples.

When you start looking for specular reflections, you see them everywhere, so you’re going to have to deal with them when you capture, process, or display photographs. Why do you need to pay attention to them?

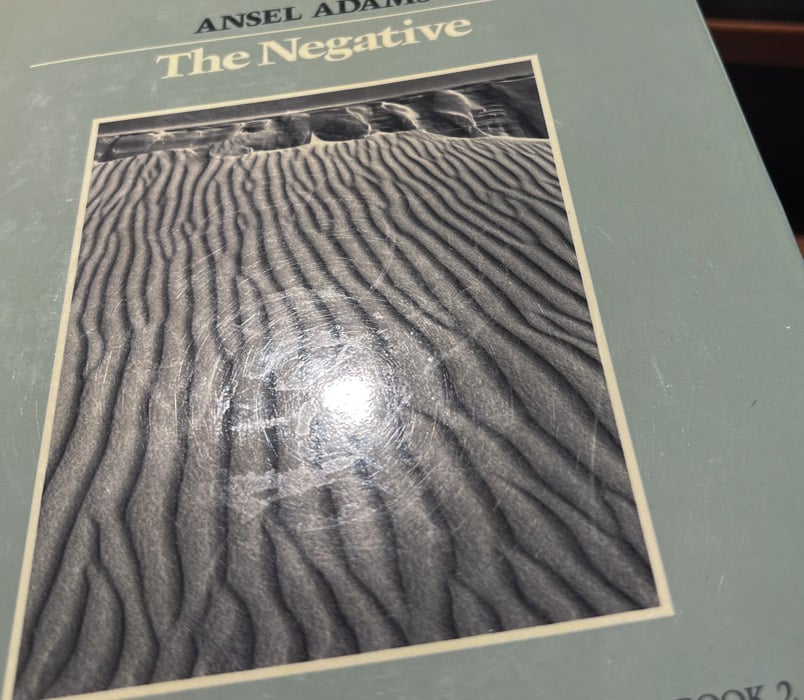

The first reason is exposure. Normal light meter calibration is performed so that an diffuse 100% reflector in an evenly illuminated scene will be safely below clipping. But specular reflections can be as bright as the light source. The correct exposure for the sun at f/11 and ISO 100 is about 20 nanoseconds. The “Sunny 16” rule says you should use 1/200 second or 5 milliseconds, which will overexpose the sun by 18 f-stops. If strong specular reflections of the sun appear in your image, you can’t practically use exposures short enough to avoid clipping those reflections, and if you managed to do that, the rest of the image would be so dark and noisy as to be unusable.

So, if you’re shooting many outdoor scenes, you’re going to have to look at the histogram and the zebras and try to sort out what’s a specular highlight that you should let clip, and what’s a bright area in which you should strive to retain detail. It’s not easy, but paying attention to specularity whenever you photograph will eventually allow you to make better choices.

The next reason is reflections that aren’t blown, but contain image content that you may wish to emphasize or suppress. Water and glass surfaces are classics here. If you want to suppress such reflections, you can use a polarizing filter. But if you overdo it, the scene won’t look natural any more.

If you’re working in the studio where you can control the lighting, then you’ll find yourself creating, controlling, or suppressing specular reflections. Here’s an example that any portrait photographer can relate to. Imaging you’re photographing a person’s face. Human skin, unless covered liberally with powder, is a fine source of specular reflections. You can make those reflections less intense by diffusing and broadening your light source, so instead of getting a small very hot spot on someone’s cheek or nose, you get a wide modestly lightened area. If you’re photographing jewelry or other shiny objects, you may wish to employ cross-polarization (one filter orientation over the light source, and another over the lens) to suppress reflections. But you’ll probably want to keep some reflections, and controlling the size, brightness, and orientation of your lights can do that.

Leave a Reply