In one of the photo boards recently, a chorus of pleas rose up to test cameras the same way as cars. There were complaints that camera testers tested under unrealistic conditions, and weren’t working pros. The whole discussion didn’t sit right with me, and I took to my keyboard, as I often do when I want to clarify my thinking.

First off, those who read this blog know that I am somewhat of a geeky gearhead, in addition to being a passionate photographer trying to make art. But most of you don’t know that I’m also a gearhead by the older, automotive definition, and have been obsessed with cars since I was 10 or 11 riding my bike to auto dealerships in September, snapping up the brochures for the new models. I’ve been into heel-and-toeing, double-clutching, rev matching, brake-fanning and other now-obsolete skills for decades, in addition to some that still apply, like trail-braking; apex hitting; late, early, and double apexes (with cars folks, it’s never late apices); and Bob Bondurant-style wheel handling.

I’ve been reading car magazines since the days when I was pestering car salesmen for brochures with my Schwinn stashed outside their showrooms. I still subscribe to three, and Apple news has figured out my interests well enough to ensure that a quarter of the news in my feed is auto-related.

So, I think I’m qualified to speak about how car magazines review cars.

Who does the reviewing

Car magazines, at least the ones that I read, like AutoWeek, Car and Driver, and Automobile, don’t as a rule review race cars, although they may run a “I drove one of last season’s F1 (or IMSA) cars, and here’s what it was like” piece once in a blue moon, and a review of something like the Ariel Atom slightly more often. They review street cars, because, Walter Mitty-esque fantasies aside, there are far more people who are interested in purchasing street cars than race cars (There is an element of car pornography in some of the car reviews, with McLarens, Ferraris, and Koenigseggs getting far more press than their sales would justify; I admit that I read those articles, too, although I am too old, poor, and protective of my marriage to ever be a customer.)

The people who review the cars are almost universally journalists, if specialized ones. Their primary skill is a way with words, and some of them, like the WSJ’s Dan Neil, are spectacularly skillful at that. A few of them have turned into credible sometime amateur racers (and one raced in the Indy 500 once), but driving skill is not what got them hired, or what keeps the readers coming back for more. Every so often a professional racer will get a few column inches to opine on racing, but top-flight racers don’t review street cars for the auto rags; they have better things to do with their time, and if racing is their long suit, writing may be a 9-high doubleton.

In photographic publications, the reviewers are likewise not professional photographers at the top of that game. I think they are close to journalists, in that they write for a living, but it is with deep sadness that I note that the standards for stylish prose are abysmal in the photography world compared to those in the car magazine universe. I doubt that the most-trodden path to getting hired as a photo reviewer includes a degree in Creative Writing and one in English Literature like Neil’s, or that a camera review site would give guest reviewer slots to someone like P.J. O’Rourke, as at least one car mag has done.

Aside: why is the best writing in newspapers found in the Sports section?

There are professional photographers with web sites that review cameras, but those photographers often have brand commitments that appear to bias what they write (when I first typed that sentence, I typed the word “promote” instead of “review”; it just slipped off my fingers, but in a sense, it fits much of the time). I’m not up to date on the site, but years ago, under Michael Reichmann, Luminous Landscape was an exception to the point I’m making here.

I think the reasons you don’t find top of their career pros working for camera review sites and mags is like the situation with car magazines: they have better things to do with their time, and writing may not play to their strengths – though the wordsmithing bar is certainly lower in the photo world.

Bias towards flattering reviews

When an automobile manufacturer introduces an all-new vehicle or a major refresh, they usually take a bunch of samples to some exotic location, take rooms in a classy hotel, rent a racetrack, round up a few racers to be instructors and nannies, and get a few execs to take time off from their day jobs. Then they pick magazines and invite them to send reviewers, all expenses paid. This situation is designed to bias the reviewers in the direction preferred by the manufacturers. The writers are not highly paid. They could never in a million years afford to stay in the hotels, eat in the restaurants, or drive some of the cars that they get to experience if it weren’t for the calculated largess of the manufacturers. They have to enjoy the heck out of those junkets. They don’t want to see the invitations cease. And they know that if they are critical beyond some invisible line, the manufacturers will think twice before inviting them to the next big unveiling.

When it comes to tests conducted away from the debut events, similarly, with a few – one that I can think of, Consumer Reports – the magazines don’t as a rule buy the cars that they test on the open market. They rely on the car makers to supply vehicles for them to test. If they upset the manufacturers sufficiently, they may find that they receive the trendy vehicles that their readers want to hear about later than their competitors, or not at all. So, faced with a vehicle that is far from marvelous, they are biased to write reviews that are less than completely candid.

Note that in both above cases, it is not necessary for the “Chinese Wall” between the advertising and the editorial departments to be breeched. If you are suspicious that that wall may exhibit some porosity, that’s a third source of bias.

When a camera introduces an all-new camera, lens, or a major refresh, they may take a bunch of samples to some exotic location, take rooms in a classy hotel, provide a well-chosen photographic venue and sometimes models, round up a few pro photographers, and get a few execs to take time off from their day jobs. Then they pick magazines and sites and invite them to send reviewers, all expenses paid. This situation is designed to bias the reviewers in the direction preferred by the manufacturers. The writers are not highly paid. They could never in a million years afford to stay in the hotels, eat in the restaurants, or use some of the gear that they get to experience if it weren’t for the calculated largess of the manufacturers. They have to enjoy the heck out of those junkets. They don’t want to see the invitations cease. And they know that if they are critical beyond some invisible line, the manufacturers will think twice before inviting them to the next big unveiling.

When it comes to tests conducted away from the debut events, similarly, the magazines don’t as a rule buy the cameras and lenses that they test on the open market. They rely on the camera makers to supply gear for them to test. If they upset the manufacturers sufficiently, they may find that they receive the trendy items that their readers want to hear about later than their competitors, or not at all. So, faced with a piece of equipment that is far from marvelous, they are biased to write reviews that are less than completely candid.

The situation with respect to the Chinese Wall is also the same.

Laboratory and real-world testing

Consumer automobile testing takes place in both a real-world environment – on public roads, long and short trips, sometimes for as much as a year – and in a laboratory one, which might include racetracks, skid pads, and disused airplane runways. It’s obvious why vehicles intended for use on public roads should be tested on such roads, and why trucks meant to tow trailers should be tested doing just that.

But why the closed-course testing of cars that will likely never see a racetrack, and whose warranty would be voided were that to occur? The answer is threefold.

First is safety. The performance envelope of most modern vehicles with any sporting pretensions at all is far, far beyond exploration on public roads without grave risk to their drivers and the general public. Even setting aside the moral issues which are by themselves sufficient, the voided driver’s licenses, pulled insurance policies, lawsuits and jail time would thin the ranks of reviewers to the point where there wouldn’t be any with much experience.

Second is precision. Testing in a controlled environment can yield quantitative data, which certainly doesn’t replace the need for qualitative information about things difficult to measure precisely, is useful to prospective consumers. Saying “The McLaren 720S will do 0-60 in 2.5 seconds” is more informative than saying “This is one fast machine.” So, when the reader sees “The Ferrari 488 will go from 0 to 60 in 2.9 seconds” you’ll know more than if you read “That red car with the prancing horse is real quick, too.”

Third is repeatability. If you take vehicles to the same or similar controlled environments over and over, and test them using the same procedures, you can compare cars across time and space. Without having the old model available and testing them side-by-side, you can say things “The new NSX chops the 0-60 time of the old one in half” or “When we weighed the new Porsche, it came in 200 pounds heavier than the old one, but the new engine means that it’s 0.2 seconds faster from 0 to 60.”

But there are limits to track testing.

One is figuring out what it means for driving on public roads. In some cases, the data is clearly not directly applicable, as is the case for top speed of powerful cars with no limiters. But in others, it’s iffy. Does the fact that the brake pedal goes soft when hot-lapping Laguna Seca mean that you’ll see any such effect in real-world driving? Probably not, but the answer depends on what a hoon you are, where you’re driving, and a few other things. It also would inform your decision to buy the car if you thought you might track it occasionally, although in that case you might opt for track pads and brake fluid in any case.

Another is understanding what differences are significant. If you’re not going to be street racing, is the difference between a 13-second quarter mile and a 12.8-second one going to make any difference on the highways? Lots of experience driving cars with known numbers helps you calibrate yourself. A lot of people looking a 0.2 second differences in 13 or 14-second cars may not have that, but I’ll bet that, proportionally, many more contemplating cars around 11 seconds or faster do.

Yet another is that many things that are important to real-world use of a vehicle are totally unimportant on the track. The layout and operation of the controls, for example. That is critical – and becoming more so with every passing year – to the operation of a car on public roads but is orthogonal to the way a car handles a racecourse.

There are many important subjective attributes of a car that can’t be quantified without a large – and prohibitively expensive – panel of testers. The user interface mentioned above is one of those. So is ride quality, steering feedback, brake feel, exhaust note, shifting precision, quality of materials, control haptics, and general driving enjoyment. For all those, we must sacrifice objectivity and precision in order to get any data at all.

Apart from safety, the parallels of the benefits of lab testing of camera and auto testing are striking.

Precision? Knowing that one lens on a particular body produces on-axis an MTF50 of 2200 cycles/picture height and another lens on a different camera gets only 1600 cy/ph using the same protocol is more useful than “This lens is very sharp” and “That one isn’t quite as sharp.” Even better if the reviewer publishes the whole MTF curve set. Even better if the reviewer – tip o’ the hat to you, Roger Cicala – tests 10 lenses and reports the statistics. Even better if the whole field is sampled. Extra points for identifying how field curvature affects things.

Repeatability applies here, too. The fact that you can quantitatively compare a new camera to older ones, or lenses to other lenses new and old, is of inestimable value over comparisons where all the compared gear needs to be in the same room at the same time.

All four limitations are similar between cars and camera testing, too.

Especially for people unused to looking at metrics of camera and lens performance, it’s hard to know what the numbers will mean in terms of real-world photography. Is a photographic dynamic range of 10 stops needed for the kind of photography that I do? Can I print as big as I want with a 24 MP camera and a MTF50 1200 cy/ph lens?

And what differences will affect my photography? Will 2200 cy/ph vs 2000 matter when I’m photographing real-world three-dimensional objects and DOF is a constraint?

Haptics, the user interface, and the like are all important to camera users, as they are to drivers. None are important in lab testing. The tester has all the time in the world to set up and perform the tests, and how pleasant or unpleasant the experience has no affect of the results. I do sometimes add testing notes complaining about or praising how easy – or not – it was to achieve critical focus, but those are basically footnotes.

Lastly, the experience of using a camera to make actual photographs is powerfully affected by things that are in practice unquantifiable. The two that come to mind are the same two as in the previous paragraph: haptics and user interface.

So, should we test cameras like cars? We already do, for better or worse.

Pros as testers

Would we be better off if we had only professional photographers for camera testers? I doubt it, just as I don’t think we’d be in a happier situation if we had only pro racing drivers as car reviewers.

To my knowledge, top racers are at once incredibly sensitive to flaws – they have to be so that they can describe what needs to be changed to the engineers who will make it happen – and uncaring, once the car is doing as well as it can do, about doing whatever they need to do to get the most out of a car as long as it’s not trying to kill them. Race car handling is balanced on a knife’s edge between speed and disaster. For street car handling, it’s more like a haystack. Any top-drawer race car driver worth his – and occasionally, her – salt would have no trouble at all taking any street car to its limits, and unless prompted, would find little to complain about, and, if the complaints were voiced, they might be couched in language incomprehensible to the average street driver. Another point is that the pros care about how a car handles at their limits. They get paid to snuggle up against those limits consistently and with precision. Street drivers usually closely approach those limits only just before they exceed them with unpleasant consequences. What seems fast to most street drivers isn’t so to racers.

There are drivers who are full-time professionals who are employed by the manufacturers to help sort out street car handling during the development of the designs. They would probably make great reviewers, but have day jobs and conflicts of interest, whether they review a car that they themselves shook down or one from some other car company.

I don’t know about pro photographers, but I suspect that there are parallels there, too.

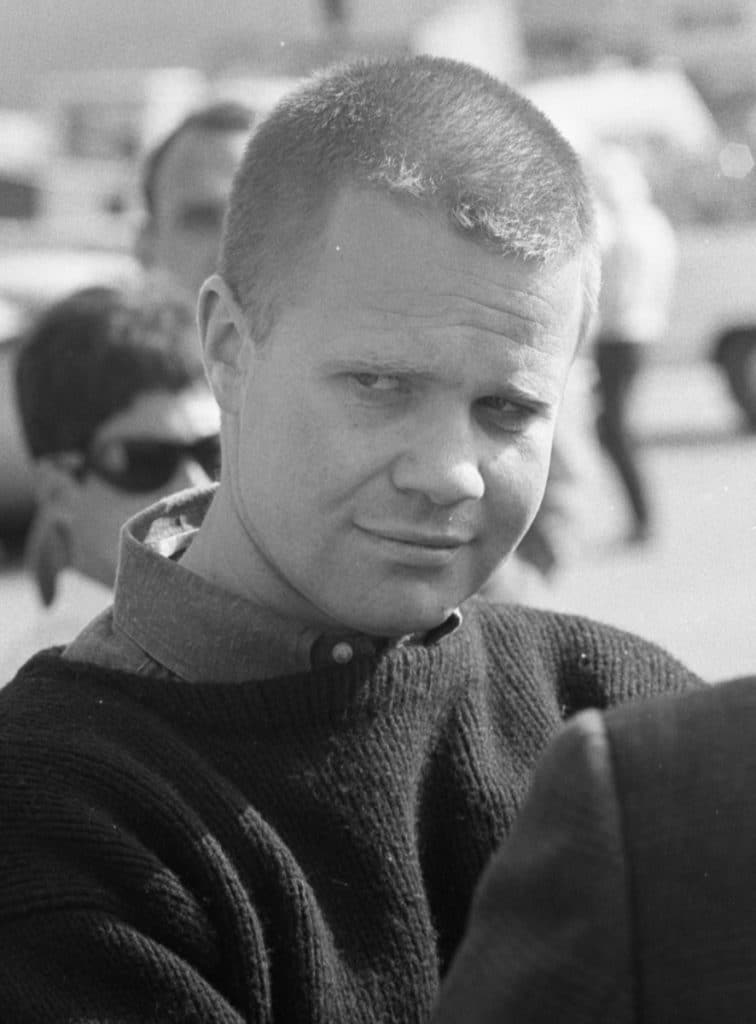

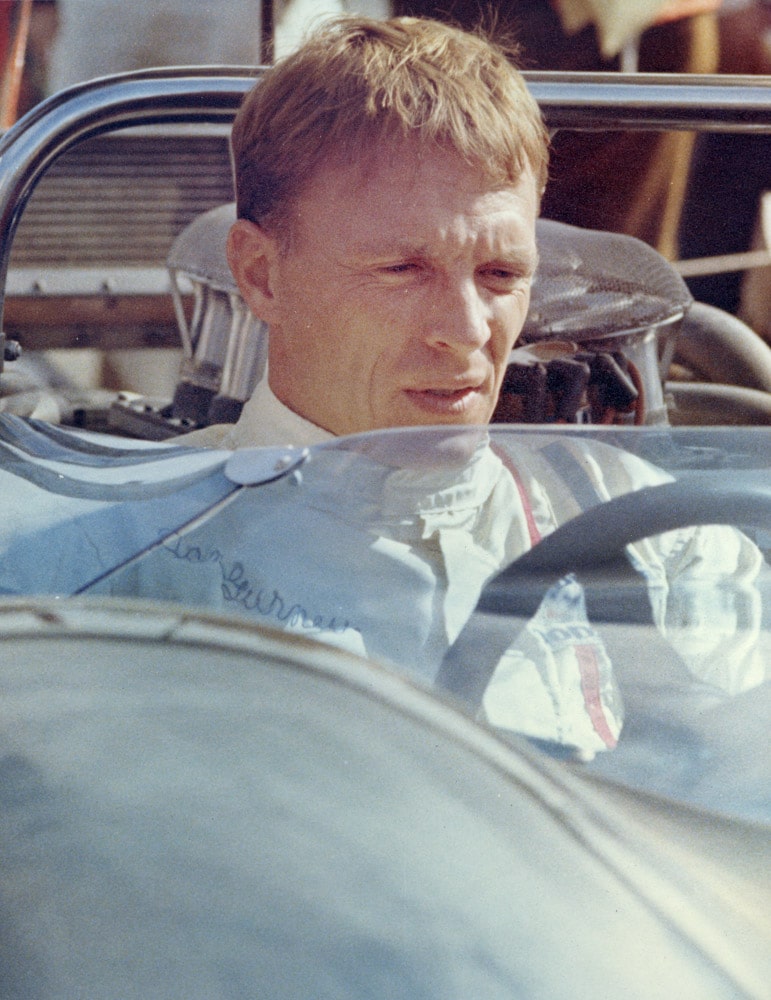

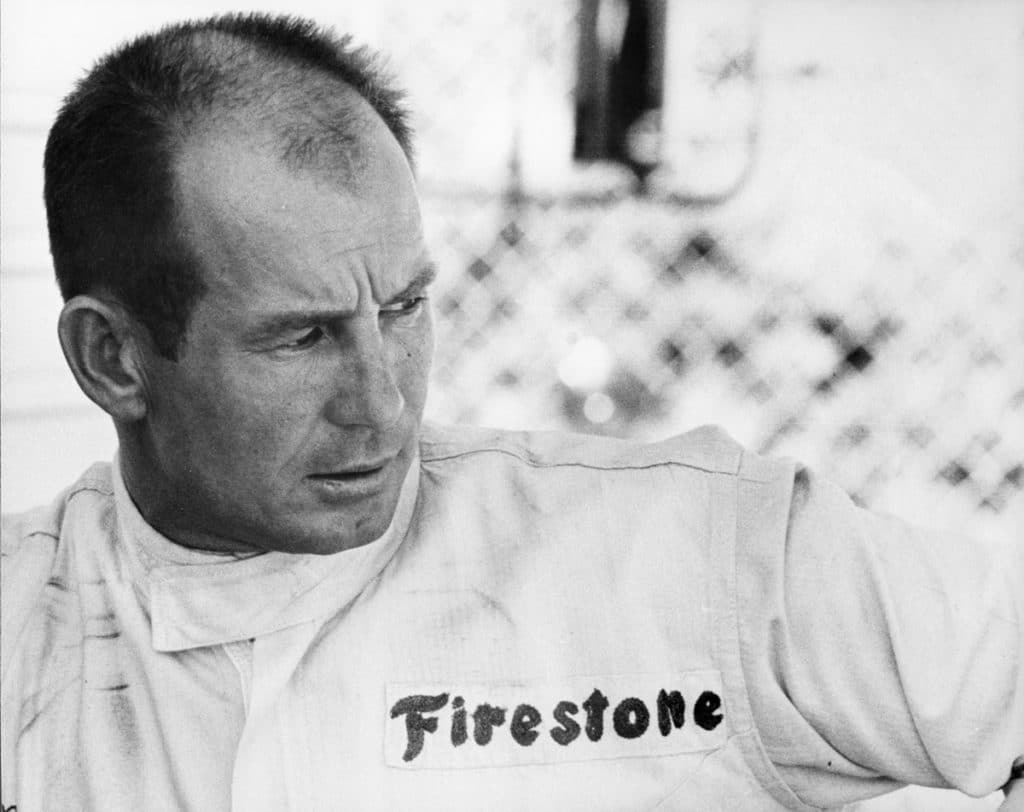

By the way, I made the pictures accompanying this post when I was working for Tom Montgomery covering the Laguna Seca USRRC and Can Am races for Competition Press and AutoWeek.

Mike Nelson Pedde says

Well said. I have no hesiation in saying that some of what you write is beyond me, but I always appreciate that you do because I learn something along the way.

It’s been a lot of years since I sat down to lunch with Michael Reichmann (and of course now impossible) but I like to think that camera manufacturers sent him equipment to review BECAUSE they knew he would be as impartial as he could be and they valued his opinion anyway.

Brian says

Fun to read and see this other side of you and your photography, thanks.

Roger Cicala says

This is so completely true and factual, yet clearly and logically laid out. Kudos Jim, we’ve needed something like this written.

JimK says

Coming from you, Roger, that means a lot. Thanks!

Andre Y says

From one petrolhead/photo enthusiast to another, this is a great essay, and makes very many important points. The professional label in photography is also overrated: there are lots of amateurs whose skills, vision, and creativity would put many pros to shame.

Bruce Oudekerk says

A buddy and I campaigned an SCCA H Production Bugeyed Sprite back in ’69 & ’70. It was abject pandemonium but one of the best chapters of my life. So thank you, Jim. Your photos bring back great memories. I suspect being a gear-head is a life long affliction.

Unfortunately…I don’t think I even owned a camera to capture that exciting time.