I’ve been working away on developing a way to digitize black and white silver negatives at high quality using a GFX 100 and/or GFX 100S (I’m going to call this operation “scanning” although I’m aware that that term doesn’t really fit). I’ve reported on this blog about some of my testing of appropriate lenses.

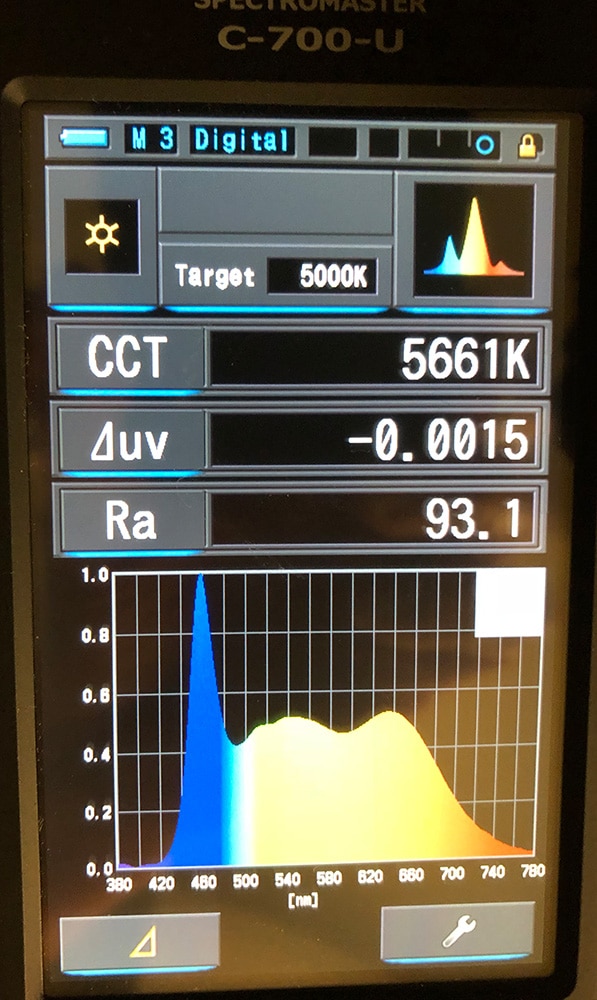

I’ve also been playing with illumination schemes, ways to hold the film flat, and mechanical assemblies. I’ll be reporting on that in more detail here. I have been talking about what I’m doing on the DPR MF Forum. On that forum, I was cautioned against using the Westcott LED panel that I’ve been employing for performing my first experiments, because the spectrum isn’t nice and smooth.

This has caused me to think about the importance of smooth spectra in film scanning, and I’ve concluded that for most uses today, and for my black and white film scanning, it’s not important at all, and may well be harmful.

I’ll use this post to walk you all through my reasoning.

We need to consider several scanning scenarios.

The first is scanning positive transparencies that have not faded, with the idea of capturing the colors of those transparencies. For this situation, and for this situation only, I agree that smooth illuminant spectra are desirable. The reason is to reduce illuminant metameric error. The spectra should not only be smooth, but it should be the spectrum of the reference illuminant of the transparency. This is not enough to get perfectly accurate colors, since the camera response to light won’t meet the Luther-Ives condition, and we’ll still have to deal with capture metameric error, but it’s in general a good thing.

The second is scanning positive transparencies that have faded, with the idea of capturing the colors of those transparencies before the fading occurred. In this case, smooth spectra are not optimum. What we want to do is capture the response to light encoded in the cyan, magenta, and yellow layers of the film. For that, we want to pick spectra that give us the maximum separation between those layers, like the spectra used in color densitometers (anybody remember those?). Once we’ve done that, we can use the spectra that the dyes had when new to restore the image. I would submit that many, if not most of the transparencies that people want to scan these days have had some fading occur.

A related scenario is scanning color negatives with the idea of reproducing the colors that would result were those negatives printed with a reference process on reference materials. That situation is similar to the faded transparency situation in that we don’t care about what the colors of the negative are, but instead we care about what the spectra of the negative has to say about the light that fell on the film. For this process, we want narrowband filters that we can use to discern the densities in each of the film’s three layers.

The last scenario is scanning black and white silver negatives. In that case, we’re not concerned about color at all, but about chromatic aberration and signal to noise ratio. This gets a bit messy, as there are subsets to consider.

If the sensor is monochromatic, we want the illuminant to have a narrow spectrum centered on the peak response wavelength of the sensor. This will eliminate the effect of longitudinal chromatic aberration (LoCA).

If the sensor uses a Bayer color filter array, as does the GFX 100x, then we need to trade off between LoCA and sampling density. If we pick a very narrow spectrum, we run the risk of exciting only one of the channels of the sensor. Say it’s the green channel. Now we will have lost the samples that we might have otherwise gotten from the red and blue channels, since they will be noisy. So we might choose two or three narrow channels. To minimize LoCA, we should avoid the very short and very long wavelengths. If we know the behavior of the lens focal plane at many wavelengths, that should inform the decision, but we usually don’t.

All of the above assumes that we control the details of the software that converts raw data to colorimetric or monochrome image files. I have worked in laboratory environments where that is the case, but most of us don’t have the time or skills to integrate our own personal algorithms into out workflow. However with the color profile generation tools available to us now, we can deal with a much wider range of illuminants that the ones usually employed.

Ilya Zakharevich says

(Due to the specifics of fora, I plan to address different points one-by-one.)

(A) Trivial, just-in-case! The “smoothness” of the spectrum is irrelevant. What MAY be important is the “smoothness” of its products with spectral sensitivities of the sensels.

JimK says

The spectral responses of the three — or four— raw channels in modern cameras are in general smooth. Likewise the spectral responses of film dyes.

Jeff Greer says

Although I did not get into the technical depths you have, I have scanned b/w negatives (mostly 6×4.5 and 6×7) using a Fujifilm 50R, Mamiya 645 120mm f/4 Macro, Kaiser Slimlite Plano for illumination and film holders I still have from flatbed days. I have holding film flat with Anti-Newton glass. I have no complaints with this setup.

JimK says

I’m trying to stay away from glass, so I don’t have six surfaces to keep clean instead of two.

Jürgen says

In 2018 at the Photokina I met a scientist from the Fraunhofer institute, which shows a possibility to photograph Small objects for a museum. He uses a phase one with an LED light from yujiintl.com.

They build LED stripes with full frame spectrum ,maybe this is a good solution to light your black-and-white films.

Fred D says

Jim:

Considering that for various reasons (including imperfect film flatness, lens aberrations, pixel-shift positioning imprecision,…), the actual performance of any camera-and-lens is likely to fall short of theoretical, at what output print size do you think that a critical eye would notice improvement from using a Fuji GFX 100S in any mode over using a Sony A7Riv in pixel-shift mode with a green band light source to digitize high-quality full-frame 35mm B&W film negatives? (For the A7Riv, assume a lens like the latest Sigma 105mm f2.8 DG DN Art macro, which has gotten good reviews. For the Fuji GFX 100S, assume a ceiling of perhaps three or four thousand U.S. dollars for the lens, ideally less, not something super-expensive and esoteric).

JimK says

Only one way to find out, and that’s to run an experiment. It will be a while before I’m ready to do that.