This is a continuation of a series of posts about adapter pitfalls and pleasures (I promise that I’ll get to the pleasures). The first four posts are here, here, here, and here.

In the last post we saw that, in spite of my intuition, at identical magnifications, that adapter tilt affected defocus blur more with short lenses than with long ones. I kept that in mind when I set up the test you’ll read about here, a test that stacks the deck against adapters. First off, I used a test protocol that is very sensitive, allowing you to see errors clearly that never would be a problem inn real-world photography. Second, I picked the shortest rectilinear prime I own, and it is sharp enough to draw blood: The Zeiss 15 mm f/2.8 Distagon ZF.2. Third, I used the lens wide open, something that you wouldn’t do in the field if you wanted corner-to-corner sharpness.

I tested two combinations: the 15/2.8 on a Nikon D850, and the same lens mounted on a Sony a7RIII with a not-very-good adapter which has about 16-18 um of tilt (it’s hard for me to measure tilt precisely).

You can read about the test here.

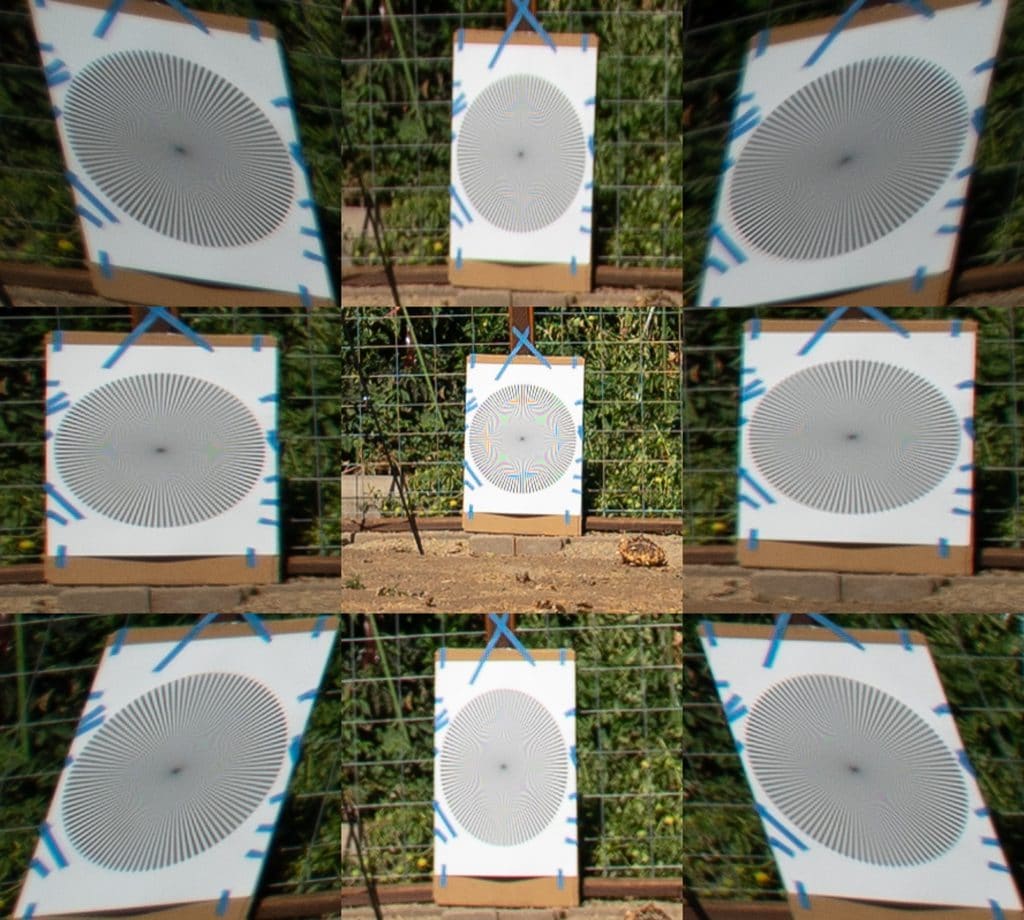

I set up the cameras 20 meters from the target. Here’s what it looked like to the Nikon:

Here are the crops, magnified to 2000×2000 pixels from a little smaller than 1000×1000, equalized for field of view, which gives the slightly-higher-res Nikon

The Nikon image is sharper in the corners and sides. But there’s still enough resolution in the Sony image to show aliasing in every star. For the great majority of actual photography, as opposed to this kind of contrived test, the Sony a7RIII and the Distagon would do just fine. For star fields, you might prefer the D850. with an adapter with 10 um of tilt, it would be even closer.

[…] This is a continuation of a series of posts about adapter pitfalls and pleasures (I promise that I’ll get to the pleasures). The first five posts are here, here, here, here. and here. […]