This is part of a series about my experiences in publishing a book. The series starts here.

A blogger discovered this series of posts, and wrote that pretty much everything that I did in getting my book out was wrong. I disagreed with some of that, but I certainly admit that this whole endeavor was a babe in the woods experience. One thing that the blogger said resonated: that if I really wanted to find out why the pages weren’t lying as flat as I wanted, I should take a book apart. The same blogger posted a disassembly of a book, which gave me an idea how it was done.

Makes sense to me. It’s a little late to do anything about what I find, but I may learn something that will help me if I ever do another book. And, what I found might help you, dear readers, should you ever be sufficiently deranged to do a book of your own.

Foreshadowing: I did find the reason that the pages don’t lie as flat as I had hoped, and it wasn’t what I thought it might be. I’m gonna bury the lead and keep it a secret until it unveils itself under dissection. Read on.

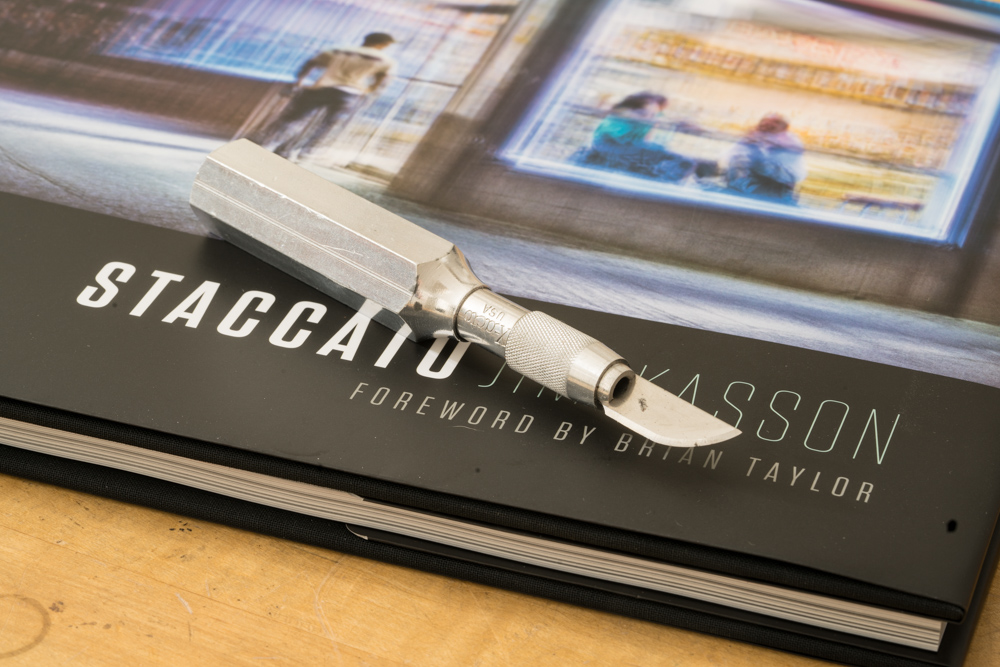

Here’s the toolkit for the disassembly:

As it turned out, I only needed one tool:

We’ll get to the flat pages part, but first I want to show you the way the dust cover works.

If we open it up, we can see the way it’s folded. This is called a French Fold.

I’ve done something unusual with the fold, with the idea of keeping it from catching on things as the book is used; the corners are rounded:

But there’s a downside to that. You can see when the cover is unfolded that there’s a stress point where the two quarter-circles come together. In retrospect, I would have been better off to go with my original idea, a forty-five degree angle. Or maybe I should have just forgotten the whole idea of trying to keep the corners from snagging. However, the covers seem to hold up fine, so I may be worrying about nothing.

Here’s the book without its dust cover:

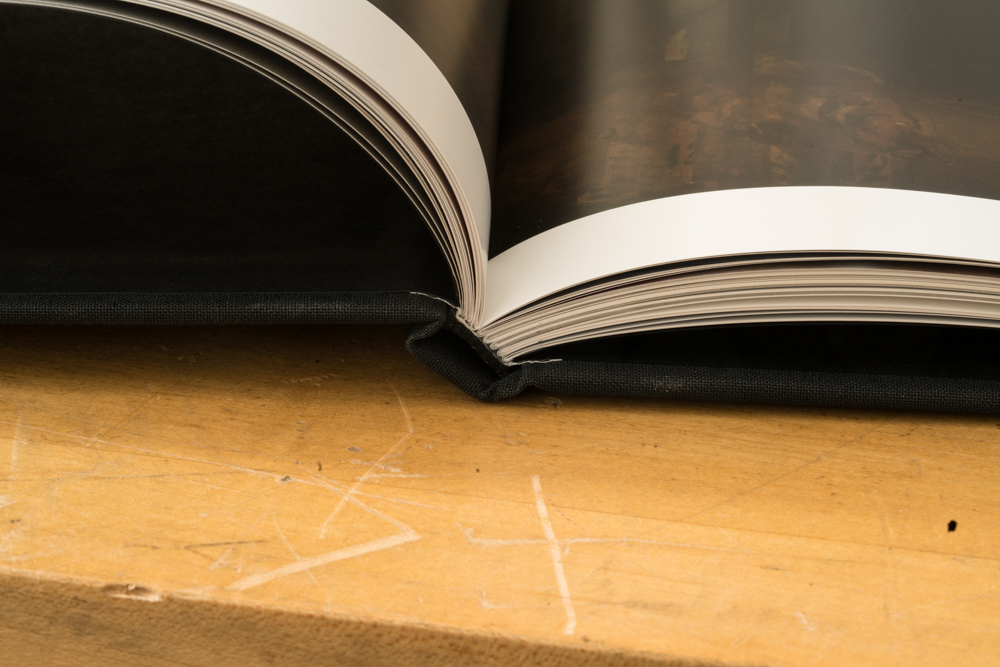

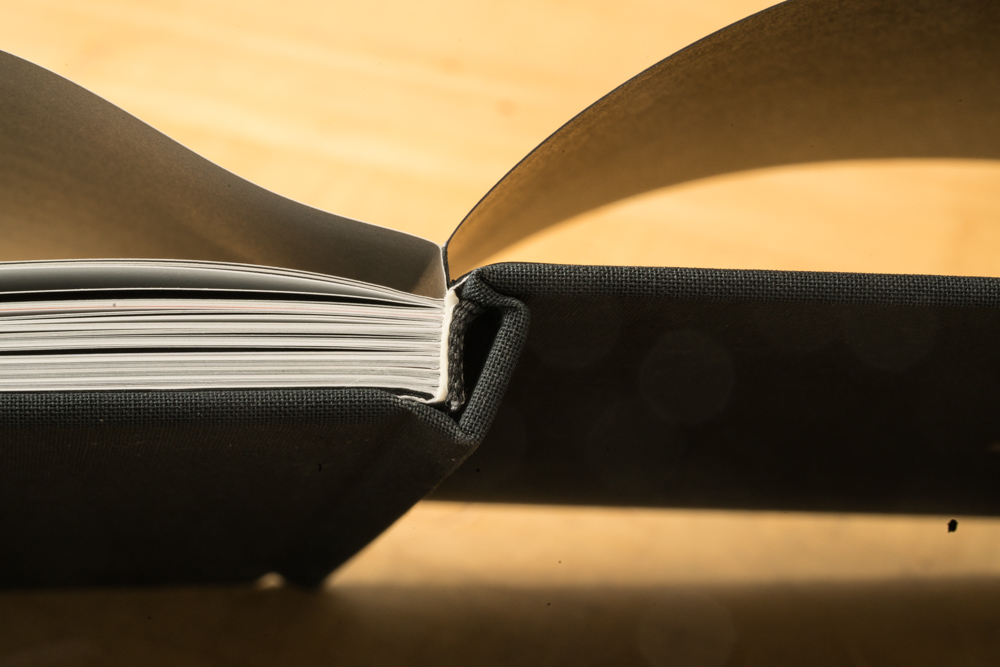

And here’s a look at the way the pages lie when a brand-new copy of the book is first opened:

After you go through the operation of gently pressing down on the pages in several places in the book that we learned in grade school, it lies flatter, and you can see the spine bending a bit:

If we look closely at the spine, we can see that the sheet of black paper that lines the insides of the front cover holds the pages into the cover. That’s called the end paper. There’s a similar piece of paper on the back cover. There’s also a piece of black cloth covering most of the end of the spine so you can’t see all of it. That’s called the headband. Its only purpose is cosmetic.

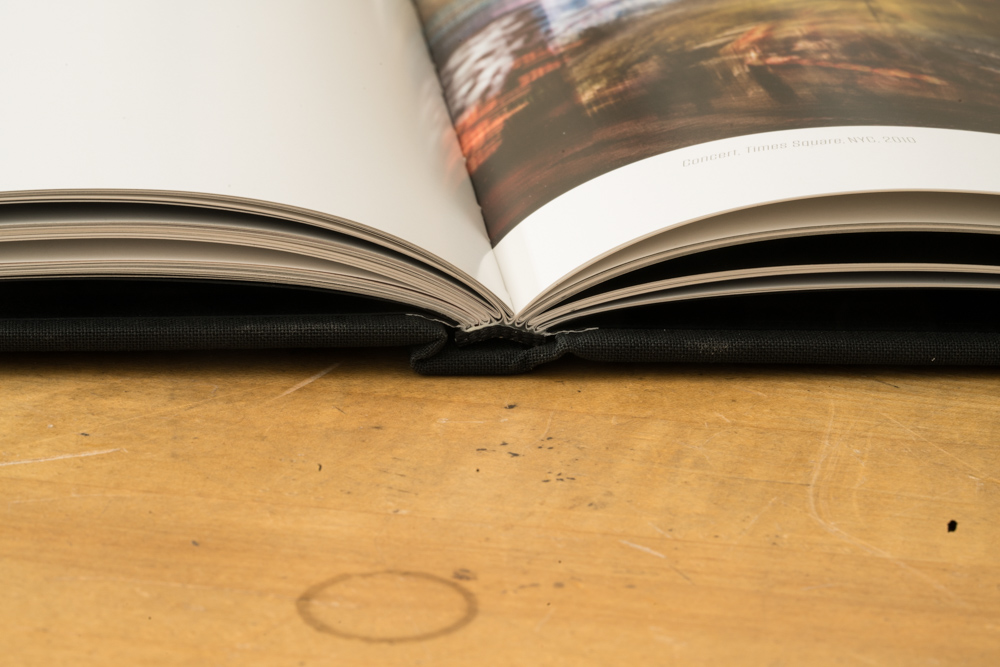

Now let’s look at the way the end paper that’s glued to the covers attaches to the pages. The end paper is folded back on itself to create thick black pages that feel like the first and last page of the assembled book. But they’re not part of the part of the book that’s stitched together itself. The end papers are glued to the first and last page of the rest of the book — aka the text block — for about a quarter of an inch. If you look carefully at the image below, you can also see a white thing connecting the text block to the covers. The white material goes between the glued-down part of the end paper and the covers of the book. So the book is held together in two ways: with the thick black paper, and with the material underneath it. That’s called the mull. We’ll get a look at that material shortly.

Note also in the image above that the interior spine of the book is not attached to the cover. It floats, allowing some bowing and thus allowing the pages to lie flatter.

Making an incision at the place where the end paper that’s glued to the cover of the book meets the spine allows the text block to separate from the cover. Note that there’s a still a piece of material that appeared to be the spine of the book when it was assembled. But it wasn’t attached to the text block along the spine of the text block. The head band is still attached to that floating spine. Although it looked like the headband was attached to the text block before we cut it open, that wasn’t the case. You can also see where the mull goes underneath the pasted-down end paper for about half an inch to the right of the interior spinc.

Doing the same thing to the other end paper and setting the text block aside, we see on the left the inside of the cardboard exterior spine of the book, with the floating interior spine inside it. We also see what that white stuff in the mull that helped attach the text block to the covers: it’s some kind of coarse cloth. The interior part of the floating spine is lined with soft cloth, probably to keep it from abrading the text block as the book it used and the two slide together.

This interior spine — I think it’s called the crash, although that may just be another name for the whole mull — is quite stiff; it’s hard to bend it.

Turning the interior spine over, we see the part of it that faced the back of the book. It looks like there was a piece of brown tape that was part of the mull and was helping to attach the pages to the covers:

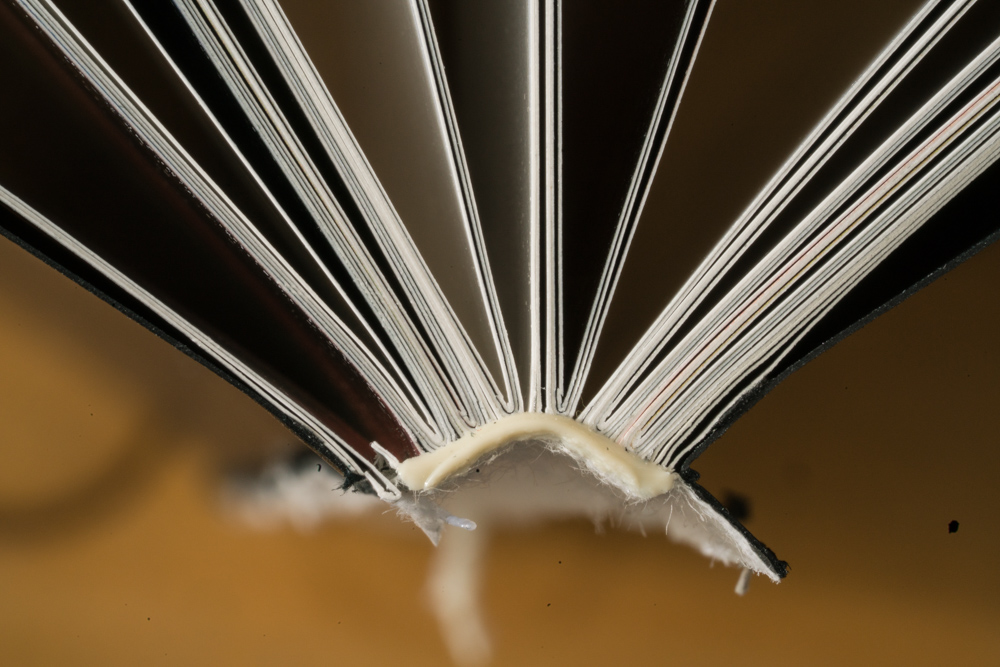

Now free of the interior spine, the text block bows a lot more than it did before, and thus the pages lie flatter:

So why did that interior spine keep the back of the text block from bowing? It wasn’t glued to the text block. The answer lies in geometry. Note how close together horizontally the ends of first and last paces of the book are in the above image. When the back of the text block bowed upwards, they had to get closer together, since the back of the text block is not materially elastic. Had the text block been attached at the first and last pages to the cover, the stiff interior spine would have kept the first and last pages from getting so close to each other. It would have had to bow by the same amount for that to happen, and it’s too stiff for that.

So, the interior spine, which is part of the mull (and may or may not be called the crash) is what is keeping the pages from lying flat. In order for the pages to really lie flat, we need a more flexible interior spine. When Jerry and I were focused on the stiffness of the glue, we we focused on the wrong thing. The glue is plenty flexible, as you can see from the image just above.

There’s another thing to consider. If the interior spine/crash/piece of the mull were more flexible, when you opened the book it would bow more, and thus the parts of the mull between the spine and the pastedown would have tension on them. If there weren’t extra material there, the interior spine still wouldn’t be able to bow, and, in trying to do so, would strain the mull and potentially shorten the life of the book. So there would have to be extra mull to allow the spine to bow, and that would have to go somewhere when the book was closed.

I’ve seen books where the spine worked the way I wanted this one to work, but I’ve never taken one of them apart and thus I don’t know the details of the construction. Maybe that’s another project. However, I don’t want to destroy any of the books that I’ve seen work right. Maybe I’ll be able to find one that I’m willing to sacrifice for the cause.

Just for completeness, I’ll go ahead and show you how the text block is put together.

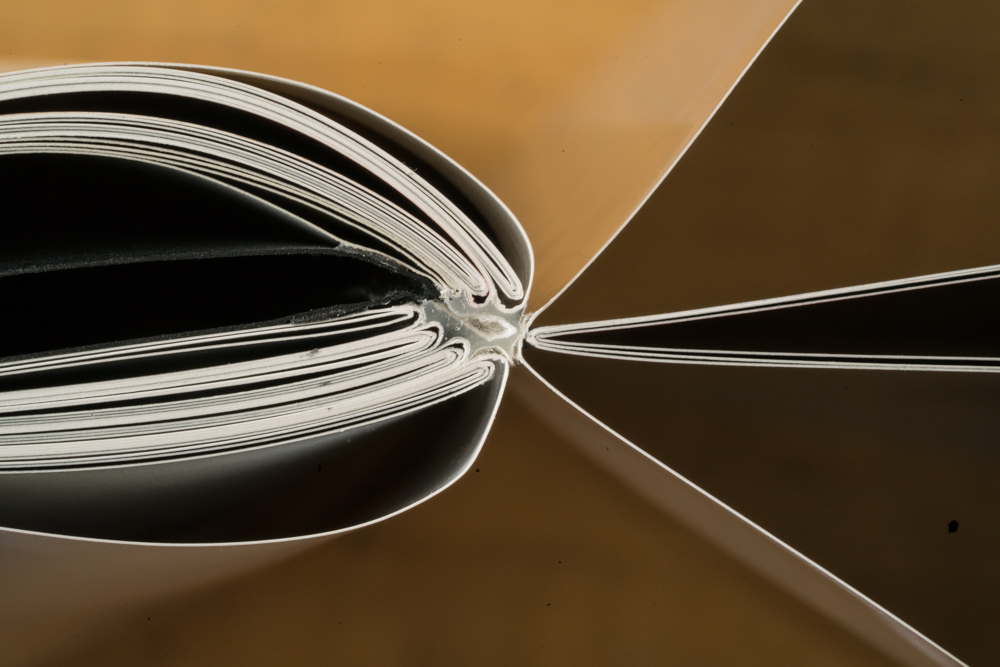

Here’s a look from one end. The back of the book is on the left. You can see the cut-away halves of the end papers. You can see the folded pages of the book are arranged for the most part in groups of four folded pages, or sixteen numbered pages in the book. When we laid out the book those constituted the signatures the book was printed on. Now that they’re cut apart and folded, they’re called quires. It’s a little hard to see, but the quires at the very front of the book have fewer pages than the ones in the rest of the book.

I’ve bent the pages so that a single quire is on the right in the following image:

The quires are sewn and glued to a flexible support to form the text block. With the knife, I cut the thread and pulled away one of the quires:

Now I can separate that quire from the rest of the text block:

Here are the four pieces of paper that form the quire:

You might be looking at what’s termed ‘spine liner’ which is, well, various materials glued or lightly tacked to the spine of the text block. This is supposed to impart the right degree of flex, neither too little bit too much.

I think of this as, essentially, building a composite. Fiber embedded in goo. But getting it right is not trivial! It may be that the thing is made ‘too stiff’ initially so that, I dunno, ten years hence it will be perfect? I’m not an expert, really, just a guy with an xacto knife and a lot of opinions.

A side note, I don’t think *everything* you did was wrong! But perhaps it seemed so, since all my remarks were complaints? Please assume that anything I did not mention was performed, in my opinion, admirably, by beautiful and brilliant people!

I apologize for any slight you felt. If I meant it, and I am sometimes a small person, I didn’t mean it personally.

Andrew, I didn’t take anything you said personally, and I certainly didn’t — and don’t — feel slighted in the least. I am flattered that you took the time to read the whole saga. I’m glad you gave me the insights that you did. Thank you.

Jim

Does this endeavor end up being yet another argument for (color managed) digital books?

This senior citizen is gradually weaning myself away from the printed page.

Definitely not. Watch for tomorrow’s post.

jim