Preface – feel free to ignore this

In 1973, I left hp to join a small computer manufacturer called Rolm with the objective of designing a set of products that would get them into the telephone business. I designed a type of telephone switching system known as a PBX. I hired the engineering team, created the system architecture, managed the project, and after 21 months we shipped the first Rolm CBX. The market didn’t know quite what to make of it. It did the switching digitally and was run by a computer. We added features to systems in the field with new software images. We maintained the PBXs remotely, over dial-up telephone lines. It had only recently been legal for customers to buy telephone gear and attach it to the switched network, and most folks didn’t know how it was all going to work. The customers were used to renting equipment from AT&T, and not being involved at all in picking the systems. The AT&T salespeople were not used to having competition or doing much besides taking orders, but they developed a great tool to use when a customer of theirs showed signed of considering buying their own system. I don’t know what the AT&T guys (and they were mostly guys) called it, but we called it FUD (pronounced as a word, not as three letters), and that stood for fear, uncertainty, and doubt, which is what they were trying to instill in the minds of those people rash enough to consider jumping ship. I could have told them some of the technical feet of clay of the CBX, but they didn’t understand it well enough to sell against it based on facts, so they started planting FUD in the customers’ minds. AT&T had always taken care of them; would this upstart do the same? AT&T ran the whole network from end to end for years, and everything was optimized to work with everything else; how could these Silicon Valley computer types ever hope to understand what it took to make a phone system. AT&T spent thousands of man-years engineering reliability into their system; Rolm made that product with fewer than 10 engineers.

At first, it worked. At least it worked on most of the customers. But some were immune to FUD, or at least greedy enough to want a system that could dramatically reduce their phone bill and provide unprecedented administrative advantages. And after a while, the be-FUD-eled phone system users learned how things were working out for the brave ones, and, like the fog burning off on a West Coast summer morning, the FUD began to clear away.

Preface, part two – also can be skipped

Sony shipped the NEX-5, an APS-C mirrorless camera, in the summer of 2010 – gosh, that doesn’t seem like 10 years ago – and I was an early adopter. With one exception, the Sony/Zeiss 24 mm f/1.8, the lenses were pretty underwhelming in the early days, so I started adapting my Leica M-mount lenses to the camera. When the NEX-7 came out a year or so later, I ditched the 5 and started doing serious work with adapted lenses. There were some problems, but the combination of a MILC and 24 MP was pretty compelling. When the full frame alpha 7 and 7R cameras came out in the fall of 2013, I bought them both. The bigger sensor had color errors due to CFA crosstalk with some M-mount lenses, and both cameras had corner smear issues with shorter, faster lenses that weren’t retrofocal. I’ve continued to use adapted lenses on a7x cameras at least as much as native lenses, so I have a lot of experience.

Finally, the on-topic part

There’s a cadre of Sony a7x users who know a lot about using adapters. We know what is problematical, and what is not. But, with Canon’s and Nikon’s recent MILC announcements, there are a bunch of folks who are new to this game. And, thanks to the Internet, there’s a lot of FUD. It’s the purpose of this post to dispel some of that FUD.

Let me limit the scope of this discussion. I’m talking about adapters that have nothing but air in the optical path. I have no experience with those that use glass there. I’m also not talking about the autofocus performance of smart adapters, which can vary a lot from adapter to adapter and from lens to lens. I’m just talking about the effect – or lack of it – on image quality that arises from the mechanical characteristics of adapters.

If you leave out fitting issues and light leaks (not seen in high-quality adapters) there are basically three ways an adapter can damage images.

- It can be the wrong length.

- It can be tilted.

- It can cause flare.

There’s also a fourth way adapters can be a problem, but it doesn’t always affect the image quality: the lens mounts can be improperly designed ot manufactured.

Let’s take these one by one.

Wrong length

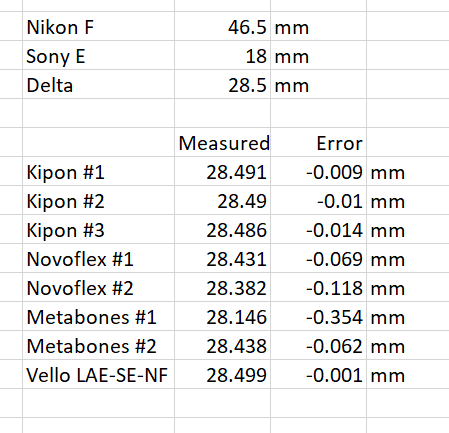

Here are some measurements I made of Nikon F to Sony E adapters:

As you can see, every one was either pretty close to right on, or too short. I have never found a quality adapter that was too long, and Novoflex, a respected and very expensive supplier, has admitted to making their adapters too short on purpose. I mostly use Kipon adapters, which are pretty close to as long as they should be.

The reason that manufacturers don’t want their adapters to be too long is that they are afraid lenses won’t be able to focus to infinity. In fact, some of them are so afraid of tolerance buildup among the body, the lens and the adapter that they make the adapter aim point to be shorter than correct.

What’s wrong with that? If you have a lens that focuses by moving all the lens elements as a group, not too much. Your distance scale won’t be right anymore, and one of the great things about rangefinder lenses is their distance scales, and you won’t be able to focus on subjects as close as you would were your adapter the right length. But your image quality will be just fine. The problems come when you’ve got a lens that uses internal element motion for either close-focus compensation or for focusing. Many of those lenses are designed to work their best only if the registration distance is correct. The Leica WATE is particularly sensitive to adapter length error and has gotten an undeservedly bad reputation as an adapted lens because of that.

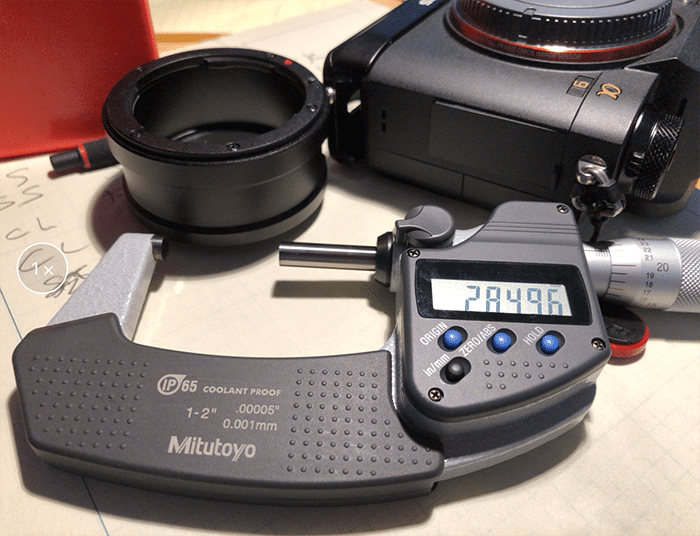

In general, it behooves you to get adapters that are close to the correct length. You can check them by mounting a short lens focusing it on a distant object, and seeing what distance the lens indicates, or you can just measure them with a dial caliper or a micrometer.

Tilted

Ideally, the two flanges on an adapter will be parallel to each other. If they are not, and the lens and camera are perfect (a big assumption), the plane of focus of the image will not be perfectly perpendicular to the lens axis. Things that are in focus will still be sharp, but that plane of sharp focus will be tilted. If you are doing full-frame captures of complex targets, adapters can sometimes be a real PITA, but I have yet to find a quality adapter so tilted that normal photography would be in any way affected unless your chosen subjects are brick walls and test charts. So this is a theoretical problem, but not a practical one. I have found that small field tilts in lenses is more common than in quality adapters.

Flare

Some adapters have shiny bits inside. This is a bad thing because stray light from the lens can bounce off them and find its way to the sensor. Some adapters have inadequate flocking in their barrels. Especially if they don’t have rectangular baffles at the back of the adapter, this can also lead to flare. Good adapters have neither of these problems.

Nikon Z users won’t have this problem, but using an adapter with a baffle intended for an APS-C size sensor on a full frame camera can result in mechanical vignetting.

Light leaks can be considered an extreme form of flare.

Lens mount issues

The lens mounts can be too tight, and damage your cameras or lenses. They can be too loose, and the resultant play in the mount can cause tilt issues. In some really extreme cases, metal shavings can get in your camera or lens.

One last thing. Don’t just throw those bare adapters in your camera bag. Put a cap on each end. That’s to protect the flanges from dings, but much more important, to prevent dust from getting in the adapter. If there’s dust in there, some of it will likely find its way to the sensor after you’ve mounted the adapter.

Once you know the ropes, adapters aren’t scary at all.

Hi Jim,

Thanks for that posting. I am quite familiar with FUD, there was a lot of that when new technology arrived.

To the extent I could, I resisted the FUD checked out benchmark data and was able to get systems appropriate for our needs.

But, I was also suffering from bias when adopting to new technology. Some of that bias may have been justified, it is always hard to know.

Getting back to adapters, I have a positive experience. But it seems that on adapters tolerances increase with price?

Tony Northup indicated that their 16-35/4L zoom looses corner sharpness on the Sony A7rII compared to Canon 5DS, especially at 16 mm. That could be caused by the incorrect flange distance of the Metabones.

I am using the 16-35/4L on my Sony A7rII and I think it works just great.

I think you’d see something else entirely if I threw a bunch of $20 Chinese adapters into the mix.